Abandon the Young in Tokyo: Yoshitarō Nomura’s The Demon and Hirokazu Koreeda’s Nobody Knows

The following is an Accepted Manuscript version of a book chapter in The Child in World Cinema (edited by Debbie Olson), published by Lexington Books (Rowman & Littlefield) in February 2018.

Introduction

In the dispiriting early postwar period, children became a recurring symbol of hope in Japanese cinema, resulting in an “enormous number of films about young people, from children to teen-agers, which filled the screens.”[1] Within this broad tradition lies a subset of films about abandoned children, a common theme in cinema as it is in Japanese fiction and popular culture. For example, there is Osamu Tezuka’s iconic manga series Astro Boy (Testuwan Atomu 1952–1968), in which a scientist sells to a circus the eponymous child-robot he created as a substitute for his dead son; Ryū Murakami’s novel Coin Locker Babies (1995), which charts the parallel lives of two young men who as infants were abandoned in coin-operated lockers at a Tokyo train station; and Takeshi Kitano’s Kikujiro (Kikujirō no natsu 1999), an absurdist road movie in which an abandoned boy is taken on a journey to find his mother by a middle-aged delinquent who, it turns out, was abandoned as a child himself.

Perhaps child abandonment remains a popular theme in Japanese fiction because of its alarming commonness in real life. Coin Locker Babies was inspired by numerous cases of infants abandoned in coin-operated lockers, which were introduced in train stations and airports throughout Japan in the early 1970s. By 1975 the phrase “coin-operated locker baby” was in popular usage, and between 1980 and 1990 there were 191 reported cases of infant deaths as a result of being abandoned in this manner.[2] In 2007, a controversial “baby hatch” was installed at a Kumamoto hospital to allow parents to legally and anonymously deposit infants they were unable to care for; it was reported that 125 were rescued via this facility in its first nine years of operation.[3] Nationwide, almost 400 children were abandoned between 2011 and 2014 alone,[4] and there here have been a number of high-profile incidents in recent years. In 2010, a young mother in Osaka boarded shut and left her apartment, resulting in the starvation deaths of her one-year-old son and three-year-old daughter trapped inside. In 2016, an incident captured international attention when a seven-year-old boy went missing after his parents left him at a roadside in a forest as punishment for throwing stones, and could not find him when they returned to collect him a few minutes later. This incident would have a happy ending, however: after a weeklong search the boy was found sheltering in a military drill field several kilometres away, and the remorseful parents were not charged.

Images of parentless Japanese children roaming alone and struggling to survive can be traced back to wartime narratives of orphans, for example, Keiji Nakazawa’s manga Barefoot Gen (Hadashi no Gen 1973–1974) and Toshiko Takagi’s autobiographical novel The Glass Rabbit (Garasu no usagi 1977), and films such as Yasujirō Ozu’s Record of a Tenement Gentleman (Nagaya shinshiroku 1947), Hiroshi Shimizu’s Children of the Beehive (Hachi no su no kodomotachi 1948) and Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies (Hotaru no haka 1988). In cinema, there has long been a tradition of focusing on the plight of children to highlight the horrors of war. Vicky LeBeau suggests that a wide range of films from across the globe, such as Roberto Rossellini’s Rome Open City (Roma città aperta 1945), Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993) and Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (El labertino del fauno 2006), adopt the child “as a figure through which to explore the legacy of war and genocide during the twentieth century.”[5] During World War II, 300,000 Japanese children and infants were killed by the atomic bombs and the firebombing of major cities, and hordes were separated from their parents and evacuated to the countryside during the American bombing campaign of the mainland.[6] Given the scale of the tragedy and its ongoing impact on the national psyche, the spectre of war would linger in Japanese fictional narratives about abandoned children even where war seemed to play no part. For example, Roman Rosenbaum argues that despite its science-fiction surface, Astro Boy is “about the archetypal abandoned child whose story is a metaphor for Japan’s war orphans.”[7]

Children of the Beehive (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1948)

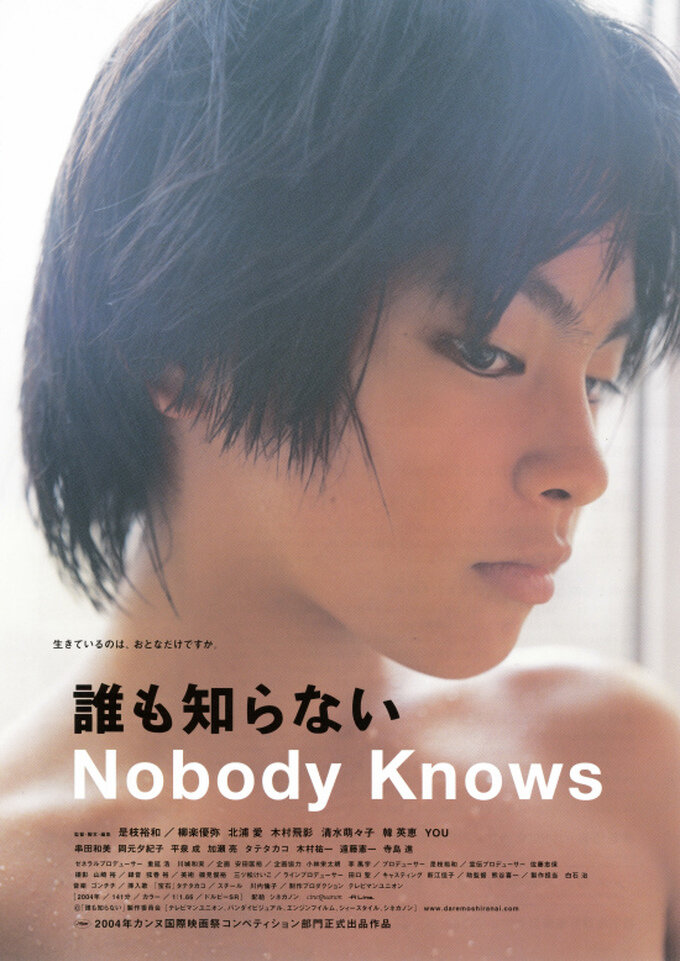

Yoshitarō Nomura’s The Demon (Kichiku 1978) and Hirokazu Koreeda’s Nobody Knows (Dare mo shiranai 2004) are two prominent Japanese films about child abandonment, set decades after the war. They both involve a set of abandoned siblings and revolve around unconventional family structures, as far as Japanese society is concerned, featuring single mothers, and fathers who are entirely absent (Nobody Knows) or else removed from the children’s lives (The Demon). Both films are inspired by actual events in Tokyo where a mother abandoned her children, and are set two decades after these events. The Demon is based on Seichō Matsumoto’s 1958 short story of the same name, which was in turn inspired by a case recounted to the author by a Tokyo detective. A struggling antique shop owner (in the short story and film, a printer) had fathered three children to his secret mistress, and after he was no longer able to pay child support she dumped the children at he and his wife’s doorstep. At his wife’s behest, he then killed or attempted to kill them (in the film, the youngest child dies in ambiguous circumstances, possibly murdered; the middle child is abandoned; and the eldest survives an attempted murder). Nobody Knows is a fictionalisation of an infamous 1988 case known as “The Affair of the Four Abandoned Children of Nishi-Sugamo” (Nishi-Sugamo kodomo okizari jiken), whereby a mother left her four children, all fathered by different men and not registered at birth, in a Tokyo apartment to fend for themselves. Nine months after their abandonment, authorities discovered three of the children malnourished inside the apartment, and the remains of an infant. They later determined that the remains were of a fifth unregistered child who had died soon after birth four years earlier, and that the youngest child had been killed by friends of the eldest sibling and buried in a forest (in the film, she dies from an accidental fall, and the fifth child is not included).

Given the length of time between the war and the period in which these films are set, war can no longer function as an explanation for child abandonment, and the abandoned child as a metaphor for wartime realities are no longer sustainable. In both films, the responsibility for the fate of the children lies primarily with the adult parents and secondarily with a Japanese society that may have contributed indirectly to the children’s circumstances. While Nobody Knows remains somewhat ambiguous in its linking of child abandonment with societal problems in Japan,[8] The Demon aligns the plight of the children squarely with the parents’ financial circumstances and the ruthless, economy-driven modern Japanese society in which they struggle to survive. Indeed, as far back as premodern Japan, child abandonment, along with abortion and infanticide, “were all well-known responses to economic inability to raise more children.”[9] While The Demon and Nobody Knows may still evoke wartime realities, these films are particularly disturbing in that they frame child abandonment as a modern, peacetime phenomenon within a prosperous nation – a result of conscious human choices rather than uncontrollable external circumstances. The depictions of extreme human behaviour in these films are palpable because they occur within a society and at a time where such behaviour may be considered highly irrational and abnormal.

The two films address their shared theme in radically different fashion. In Nobody Knows, Koreeda privileges the viewpoints of the children, accentuating their immediate everyday experiences through close-ups, repetition and symbolism. In The Demon, Nomura prefers to maintain distance, frequently abandoning the children within the mise-en-scène in an echo of the narrative, and furnishes the film with tropes that have seen it compared to a horror film.[10] The narrative focus of the two films is also in inverse. Koreeda’s film is about children who are in desperate need of parental support, while Nomura’s film focuses on parents who are burdened with children that they are desperately ill-equipped – financially, morally and emotionally – to care for. Consequently, the trajectories of the principal characters are also in inverse. Akira (Yūya Yagira), the preteen protagonist of Nobody Knows, is forced to fast-track his childhood and assume adult responsibilities to ensure his family’s survival. In The Demon, Sōkichi (Ken Ogata), the father, regresses throughout the narrative, losing his civilised veneer, and is ultimately revealed to be more childish than the children.

Tellingly, both Nomura and Koreeda take significant liberties in adapting the events on which their films are based, which in fact unfolded in much bleaker fashion than what is shown on screen. Both The Demon and Nobody Knows can be understood as examinations of extreme human behaviour and societal conditions that paved the way for child abandonment (and worse), but they also embed these seemingly despairing narratives with a degree of faith and optimism, tapping into the broader postwar cinematic tradition in Japan in which children represent hope and not misery. This chapter considers how Nomura’s and Koreeda’s films use the image of the child as a mirror to reflect and critique contemporary realities within Japan, while they simultaneously and defiantly uphold the child as a symbol of resilience and hope.

The Demon

The contrasting aims of using children as symbols of hope and to highlight ills in the adult world are foregrounded in the opening scene of The Demon. In the first shot, Nomura trains the camera on flowers in a garden while the sound of cicadas and a boy’s voice can be heard. A focus-push draws attention to the background where a six-year-old boy, Riichi (Hiroki Iwase), plays with toys next to a house. In the following shot, the camera tilts down from the ceiling of the house and settles on a younger girl, Yoshiko (Miyuki Yoshizawa), playing next to her toddler brother Shōji (Jun Ishii) on the veranda. A series of shots of each of the children shows them amusing themselves in a carefree manner, and in his cot, Shōji activates a music box which plays the first of many iterations of a haunting fairground-esque melody heard throughout the film. So far, these opening shots seem to introduce a conventional story centered on children and appear to celebrate their innocence, playfulness and freedom.

A cut to a wide shot looking past the children and into the house reveals their mother, Kikuyo (Mayumi Ogawa), in the background. The vitality of the earlier shots is transformed by a static medium close-up of her seated inside the house, troubled in thought and fanning her sweaty face. As the perspective shifts suddenly from the children to the parent, from outdoors to indoors, and from movement to stasis, the seemingly straightforward images and sounds of the children playing gain a highly subjective quality. The offscreen sounds of the children and the cicadas now seem too loud; irritatingly so. The music box melody, detached from its source and playing over Kikuyo’s exasperated face, seems to mock her frustration. When Nomura cuts to a wide shot from behind her as she watches the children, the colours, props, and movements in the background register as annoying clutter. In an instant, Nomura efficiently reframes the subject of the film: The Demon is not about children but about the adults who are burdened with them. This focus will determine the narrative and formal approaches applied throughout the film and, with only a few exceptions, Nomura does not deviate from it.

A similar contrast between parent and children is repeated moments later during the credit sequence, which unfolds over the family’s journey to Sōkichi’s house (where Kikuyo will confront him over his failure to provide financial support, and where she will dump her children). What is different here is the manner in which the contrast is made: the opening scene is highly fragmented and relies on editing for its meaning to be established, but thereafter Nomura’s filming style relies mainly on his arrangement of the mise-en-scène. Riichi and Yoshiko are kneeling on the seat inside a train and are watching the green scenery pass by outside the window, which fills almost the entire image. As Riichi remarks, “Mum, look there are trains!”, the camera pans left and shows Kikuyo holding Shōji and staring into space with an angered expression. She appears boxed in – seated in relative shadow next to a hand railing and between the carriage wall and the window, the edge of which divides the frame equally – and fails to register her son’s words or the beauty of the scenery outside. This division between interior and exterior spaces will be emphasised many times throughout the film. The children constantly desire to be outdoors but they will mostly remain confined indoors, where they will bear witness to the bitter adult conflicts that will eventually lead to their family’s downfall.

After the train arrives, Nomura uses a series of wide shots to show the remainder of the family’s journey by foot. In each of these shots there are plenty of other commuters visible, but practically all of them are travelling in the opposite direction to Kikuyo and the children. The subtle arrangement of the mise-en-scène and the movement of the extras frame Kikuyo’s family in opposition to the rest of society: they are different to everyone else and their journey is against its flow. This visual motif is reiterated several times throughout the film when characters are outdoors in public spaces – for example, during Sōkichi and Yoshiko’s journey into Tokyo (where he will abandon her at the observation deck of the Tokyo Tower); when Riichi later runs away from the house to try and find his mother; and during a scene at the playground, which becomes emptied of children when their mothers call for them go to home, leaving behind only Riichi and Yoshiko in the shot. The motif is also reinforced abstractedly in a scene where Sōkichi takes the children to the fair: they stand together in front of a novelty mirror that distorts their features, and Sōkichi seems disturbed by the grotesque family portrait presented in front of him and by his realisation of the children as “monstrous intrusions into his life.”[11] Significantly, besides Sōkichi’s employee Akutsu (Keizō Kanie) and the police who are later dragged into the narrative, there is very little interaction shown between the central characters and other people throughout the film’s 110-minute running time. The tone is set in the inconspicuous early wide shots, where Nomura isolates the family within a bubble from which they never emerge.

Predictably, the sudden appearance of her husband’s secret mistress and children at her doorstep infuriates Oume (Shima Iwashita), Sōkichi’s wife of seven years. After Sōkichi tries in vain to shuffle them away, Oume invites them all inside to discuss the situation. Kikuyo then reveals in flashback how Sōkichi seduced her at the restaurant where she worked, how the children came to be, and how desperate their predicament had become after he stopped providing financial support (Sōkichi blames the fact that business has been slow since a fire destroyed his print shop). The flashback intercuts with Kikuyo’s recounting of the story in the house, depicted on each occasion by a wide shot that resembles Ozu’s signature “tatami shot” as seen in his numerous family dramas: a static shot aimed perpendicularly into the room at a height of about two to three feet above floor level, in which the characters are precisely configured at various depths of the image (the focal length here also approximates the 50mm lens size preferred by Ozu).[12] Here, the chabudai (a short-legged table seen in traditional Japanese homes) is centered in the frame, Oume sits at the left and Sōkichi on the right in the middle distance, and Kikuyo sits on the far side facing the camera, holding Shōji and with the other two children seated beside her.

As Kikuyo’s story unfolds, the orderliness of this iconic framing disintegrates. Yoshiko taps impatiently at her mother’s thighs as she argues with Sōkichi, Shōji starts crying in Kikuyo’s arms, and Oume fidgets under the table and then begins fanning herself erratically as her irritation grows. The stillness is broken in a flurry of movement as the tension spills over. Kikuyo passes the crying toddler to Riichi who walks into the kitchen with his sister to calm him, Sōkichi lowers his head and begs Kikuyo for forgiveness, and Oume slams the fan onto the table and springs to her feet. Nomura cuts to a close-up of Oume’s face from the opposite side of the table and pans quickly and abruptly as she strides over to her husband, kneels next to him, and begins slapping him repeatedly. The sudden violence prompts a collective reaction shot of the children. It is the first time the editing privileges their viewpoint, and its use here to depict their response to rash adult behaviour establishes the way in which it will be used sporadically throughout the narrative, which otherwise unfolds mainly through the adults’ perspectives and via the careful arrangement of the mise-en-scène.

The following shot is an inversion of the previous wide shot of the whole room, filmed from the opposite side. This time the characters are configured so that they are separated by both the image’s depth and their position in relation to the camera. The children are in the foreground with their backs to the camera and watch as their father is repeatedly slapped and berated by his wife in the background. Their mother, also with her back to the camera (and to her children), sits quietly and motionlessly in the middle distance between the two groups, no longer visually associated with either. It is as if the composition has become a parody of Ozu’s signature shot, containing within it a family that has already imploded. Accordingly, in a short while Kikuyo will leave behind her children and disappear into the night, not to be seen again.

The remainder of the narrative observes in grim detail the unwilling parents – a pairing of a meek and pathetic father with a hostile and jealous surrogate mother – as their attitude towards the children shifts from frustration to murderous intent. This regression, and the sheer inadequacy of Sōkichi and Oume as parents, is emphasised by a series of scenes in which they perform increasingly grotesque variations on parenting. When Sōkichi needs to change Shōji’s diaper for the first time, he is useless and needs the help of both Akutsu (who throws him a rag to wipe up the spilled urine) and his two other children to complete the task. When Sōkichi is later feeding Shōji, business matters intervene and Oume forces him to stop; again, Sōkichi is compelled to ask Riichi and Yoshiko to step in and help. And when Oume drags a sobbing Yoshiko to her father and complains that her hair stinks, she chooses not to wash it but instead pours laundry powder over the child’s head, leaving Sōkichi to clean up the mess. Later, Yoshiko’s abandonment and Riichi’s attempted murder will be founded on parental deceit, with Sōkichi luring them with promises of play and adventure (an excursion into Tokyo and a trip to the ocean, respectively).

In one of the film’s most disturbing scenes, Oume walks in to find Shōji unsupervised at the table, playing with food and spilling it everywhere. She grabs a handful of cooked rice and begins force-feeding him, shouting, “Eat, you brat!” Sōkichi enters the room and is shaken by his wife’s behaviour, but looks on impotently as Oume tells him that this is what assertive parenting requires (“You spoil him! I’m teaching a lesson!”). Only Akutsu’s intervention puts a stop to the abuse, and he rebukes Sōkichi for his failure as a father as he snatches the toddler from Oume’s grasp (“Do something! He’s your kid!”). Shōji soon dies in ambiguous circumstances, and it is equally suggested that the death may have been caused by health complications arising from this incident, or a possible asphyxiation murder at the hands of Oume (Shōji is found unconscious under a thick sheet which had previously fallen off a shelf next to where he sleeps and covered him; both Shōichi and Oume had seen and registered the earlier event). The force-feeding scene is particularly disturbing not only because of the act depicted but the ethically problematic manner in which it has been filmed. Rather than suggesting the abuse, Nomura shows a large portion of the act in a shot where we can clearly see Oume shoving rice into the distressed toddler’s mouth; Phil Hoad states that the shocking scene “shatter[s] what’s perhaps the last remaining cinematic taboo: the direct depiction of cruelty to children.”[13] In a later variation of this scene, Sōkichi takes Riichi to the zoo after having been ordered by Oume to kill him using potassium cyanide. He initially struggles to commit the deed, but finds an opportunity at an uncrowded area of a temple where he gives his son a bun laced with the poison. When Riichi refuses to eat it, Sōkichi loses his temper and begins violently shoving it into his mouth, but the arrival of two passers-by snaps Sōkichi out of his stupor and he begins to weep (amazingly, Riichi then attempts to console him). Not only are Shōichi and Oume incapable of performing the most basic rituals of parenting – changing nappies, washing, playing, feeding – these rituals become the very methods by which to get rid of the unwanted children.

As can be seen, the image of the child in The Demon is used primarily to highlight and contrast the adults’ repellent behaviour. With the exception of the occasional shots representing the children’s (usually Riichi’s) reactions to unfolding events, Nomura prefers to show the children from the adults’ perspectives, or more neutrally, so that they become just one of many visual elements among the mise-en-scène. Occasionally, these two approaches overlap. In a prelude to Sōkichi’s second and final attempt to murder his son, Nomura films Sōkichi in close-up as he watches Riichi standing at the edge of a clifftop by the ocean; Sōkichi’s penetrating expression, glimpsed nowhere else, bares for the first time the inner, murderous “demon” of the film’s title. As the score climbs to a crescendo, Nomura cuts to Sōkichi’s perspective: a wide shot of Riichi from behind, standing and looking over the edge. In a shot that blurs realist representation with subjective imagery bordering on abstraction, the camera then zooms in to a medium close-up of Riichi, while in front of him waves crash and the late afternoon sun reflects intensely off the water – almost too intensely, as if the sea were on fire.

Nomura achieves a similar blurring effect using the aforementioned music box, whose melody is repeated many times throughout the narrative in different instrumentations (and which sometimes blends seamlessly into the main musical score). It is heard several times as a diegetic sound but also as non-diegetic music – and it is often made unclear as to which it is. For example, at the fairground scene Nomura uses a version of the melody performed on a calliope, which sounds fitting for the location and which integrates perfectly with the other environmental sounds. Later, when Sōkichi and Oume are tidying the shelf next to where Shōji died, Oume accidentally drops the sheet onto the floor and the melody begins to play; what initially registers as music on the soundtrack (used to highlight the couple’s horror and guilt as they stare at the sheet) is revealed to be the sound of the music box itself, heard by the couple in the room (they search for it feverishly and find it among the shelves). Similarly, after Sōkichi abandons Yoshiko at the Tokyo Tower and runs out on to the street, something makes him stop and look back. He flees as if he saw a ghost when the lights on the tower suddenly flash on, accompanied by the melody – which in this context is a highly subjective rendering of his feelings of guilt but which seems to be “heard” by the character nonetheless. In these instances, it is a sound associated with children, rather than their image, that emphasises the adults’ thoughts and behaviours.

As the film progresses, Nomura makes it apparent that financial hardship underlies Sōkichi and Oume’s murderous behaviour, just as financial hardship was the immediate reason for Kikuyo abandoning her children. During Sōkichi’s cross-country trip to the ocean to murder Riichi, Nomura cuts back to Oume in the print workshop. The image of an exasperated Kikuyo at the start of the film reverberates in this scene, in Oume’s sweaty and exhausted face as well as the relentless offscreen sounds of the machinery chugging away around her. In fact, Nomura keeps Oume confined indoors for almost the entire film (she is seen outside only next to the entrances to the house), constantly trapping her within a cluttered mise-en-scène and surrounding her with the sounds of machines. Likewise, Sōkichi leaves the house only when he has a chore relating to his work, or a chore relating to getting rid of the children. Although the children sometimes go outdoors to seek respite from the stifling atmosphere of the house, being outside is otherwise framed as a luxury that the adults cannot afford as it prevents them from working and earning an income. It is also significant that there is no distinction between Sōkichi and Oume’s home and workplace as they are both housed in the same building; over the course of the narrative, the interior space of the couple’s home/workshop comes to be equated with unending work and struggle. However, it is also suggested that financial hardship is not unique to this household. When the unassuming and hardworking Akutsu quits his job towards the end of the film, he cites as his reason the need to care for his elderly parents and sick son in his hometown. “Everybody’s struggling to get by,” Sōkichi remarks, at a point when he still believes he has succeeded in murdering his son. It is this acknowledgment which suggests that money cannot be blamed entirely for Sōkichi’s actions, and that at the end of the day, he still had a choice.

Nonetheless, Nomura eventually locates the financial pressures faced by Sōkichi within a wider context of an economy-driven postwar Japanese society – one which may have had devastating intergenerational effects. At a country inn on the night before he tries to murder his son once and for all, a drunken Sōkichi tells Riichi about his own upbringing, which has revolved around work and little else. During the scene, Sōkichi reveals the tragedy underlying the whole film: he was abandoned as a child himself. His father disappeared before he was born, his mother left him when he was six, and he was passed from relative to relative (all of whom were poor) before ending up in the care of his uncle, who put him to work as a printer’s apprenticeship at the age of ten. When he was due to receive his first paycheck, he was dismayed to learn that there was none, for his uncle had borrowed years of pay in advance from the employer to pay off debts. His uncle then abandoned him, consigning Sōkichi to a life of work. And in this way, Nomura aligns hard work – the pride of Japanese society in the postwar period as it reintegrated into the world community and became an economic superpower – with something akin to slavery.

At the inn, Sōkichi also boasts pathetically to Riichi that he is the best lithographic printer in Japan, and shows off his hands which have become smooth after many years of polishing limestone. The irony is a cruel one: expert printer he may be, Sōkichi’s financial struggles, which are about to lead him to the point of attempting to murder his own son, are largely due to the fact that his practised printing method has become woefully obsolete. Earlier in the film, Sōkichi pleads to his banker for a loan so that he can upgrade his equipment and remain competitive, but is denied due to his poor credit; it is also implied that he and Oume have resorted to various unethical business practises to keep their failing business afloat. And it is Sōkichi’s outdated printing method that eventually brings him undone. After Riichi’s miraculous survival (he is caught in a tree after Sōkichi drops him off a cliff), the police are having little luck in identifying his killer-to-be (Riichi refuses to reveal his father’s name or address, and Oume has torn off all the tags on his clothes so that they cannot be traced). By coincidence, a printer delivering business cards to the police station notices the shard of lithographic limestone that Riichi had in his possession and remarks on its rarity; this innocuous item becomes the key piece of evidence that leads to Sōkichi’s arrest. In the end, Sōkichi was unable to keep up with pace of the times and pays the price.

Although Riichi seems to revert to a naïve child during his father’s confession about his own childhood – he is distracted by his hermit crabs, as he is with his toys in the opening of the film, and appears not to understand let alone listen to his father’s words – there are previous moments in the narrative which hint that he is actually sensitive beyond his years to the pressures faced by adults. During their visit to the fair, Sōkichi offers the children a second turn on a train ride but Riichi declines, telling his father, “You’ll have to pay again.” On the bullet train, Riichi comments that the fare must be high and also lies to the ticket inspector about his age so that his father can avoid paying. The meaning of Riichi’s alertness to the cost of things is twofold: he has an ingrained awareness of how money should be spent carefully, affirming the financial hardship that his mother endured before the narrative begins; more importantly, it also reveals his own maturity and compassion, and his empathy for the difficulties faced by his parents.

Perhaps this explains the forgiveness he repeatedly shows towards his father. As described earlier, Riichi consoles Sōkichi as he breaks down in tears, only moments after his attempted poisoning. He also refuses to cooperate with the police after his attempted murder, even when his father is arrested and brought face to face with him at the police station. Riichi stands tall and refuses to budge as Sōkichi drops to his knees and weeps for forgiveness, before being taken away. Despite the many horrors depicted in the narrative, Riichi’s own abandonment by both parents, and the eventual disintegration of his family which sends him towards an uncertain future in state care, it is ultimately suggested that a cycle may have been broken. Unlike his father, this is a child who may grow up to be a strong and responsible adult – one who will not repeat the errors of the previous generations.

Nobody Knows

Koreeda’s Nobody Knows begins with a brief prologue set on an empty train at night. At the far end of the carriage is a preteen boy, Akira Fukushima, sitting opposite a young woman whose face cannot be seen. Koreeda cuts to a close-up of the boy’s hands clutching a pink suitcase, and then to his face, which looks down with a melancholic expression; his hair is long and unkempt, and his shirt is tattered. The film’s title is shown on screen as the lights of the city pass by outside the window. The narrative flashes back to Akira (looking slightly younger and decidedly cleaner) and his charismatic mother Keiko (played by singer and TV personality You) introducing themselves to the landlord and landlady of their new apartment. Keiko explains to the couple that her husband works abroad and that usually, only her sixth-grader son and she will be staying at home.

Her comments are soon shown to be false. Keiko is in fact a single mother and has three other children besides Akira, none of whom attend school: ten-year-old Kyōko (Ayu Kitaura), seven-year-old Shigeru (Hiei Kimura) and four-year-old Yuki (Momoko Shimizu). It is later established that the four children are in fact half-siblings, fathered by different men. In the following sequence, Shigeru and Yuki are literally smuggled into the apartment in suitcases by unknowing removalists. Kyōko, who is too big to hide in the luggage, waits at the train station until Akira comes to retrieve her at night and sneaks indoors when the coast is clear. During their first dinner at their new home, Keiko clarifies the household rules: the children must stay quiet and remain inside the apartment, only Kyōko can sneak out onto the balcony to do the laundry, and only Akira is permitted to leave the apartment – and it is he who will be in charge while Keiko is at work. And so begins the story of an unconventional family, the existence of most of whom nobody knows.

At first, the family’s life is harmonious enough. The younger children familiarise themselves with their new home and Akira comfortably (re)assumes his role as family guardian – shopping, cooking and cleaning – while Keiko spends most days working, and nights with a new lover. On her day off, the family spend their time together in the apartment and enjoy each other’s company. However, Keiko reveals to Akira that she has fallen in love (“Again?” he responds) and disappears soon after, leaving behind some cash and a note for him to look after the others. In their mother’s absence, Akira continues to care for his half-siblings so that they can live their lives as normal but soon, funds begin to run low. Then Keiko suddenly reappears, bearing gifts for the children and oblivious to how precarious the children’s situation had been. It turns out to be a brief visit only: leaving behind more money and with a promise to return by Christmas, she packs her bags and disappears again – this time, never to return. For the rest of the film, Koreeda depicts the children’s increasingly desperate situation as the household’s money dwindles and eventually disappears.

As with Nomura’s portrayal of the childish father in The Demon, Koreeda complicates the viewer’s sympathies in relation to the children’s mother. Keiko’s selfish behaviour triggers a tragedy but she is no simple villain, and unlike Sōkichi in The Demon, she does not appear to be struggling financially and thus her decision to abandon the children seems unmotivated by money. Although she is presented as a somewhat irresponsible mother even before she leaves – she comes home late and drunk, and the children are largely left to their own devices – she clearly loves and is loved by her children, as shown in the early domestic scenes. However, Koreeda suggests that Keiko’s life has long been a struggle tipped against her. In an early scene, Koreeda shows Akira watching her as she cries in her sleep, until she springs awake with the cheerful demeanour that she has trained herself to display in her everyday life; it is the closest the film comes to uncovering the emotional pain underlying her character. Keiko is compelled to conceal the existence of her children from her lover (whom we never see), just as she is compelled to conceal their existence from the landlord, landlady and neighbours (the landlord mentions to her how troublesome young children can be due to the noise they make, and Keiko later indicates that they were evicted from their previous apartment because of Shigeru’s tantrums). Koreeda implies that Keiko’s deception may be a necessary one: it is difficult, if not impossible, for a single mother of four children to find an apartment to rent, let alone find love. Although Keiko will succumb to the temptation of a new life with a new lover and abandon her children, perhaps she is not entirely to blame; after all, each of the children’s fathers abandoned all of them long ago.

The Japanese society that Koreeda depicts is one which is unwilling to accommodate an unconventional family like hers. The most direct examples of this can be seen in the callous attitudes shown by two ex-lovers of Keiko when Akira approaches them for help. When coming close to running out of money during his mother’s first period of absence, Akira visits the two men, both possible fathers of Yuki, at their workplaces (a taxi depot and a pachinko parlour, respectively). He discovers the first man (Yūichi Kimura) napping in his taxi, is too polite to interrupt him, and patiently sits and waits outside the vehicle. The man initially ignores Akira after he wakes up, and when Akira is invited into the taxi it is as if only to conceal his presence from the other drivers. Although the man seems to accept that he is Yuki’s father, he checks his mobile phone disinterestedly throughout their conversation, barely responds to the news that Keiko has been gone for a month, and Akira eventually walks away with no money. When Akira visits the second man (Kenichi Endō) at the pachinko parlour, the man notices him and motions for him to wait outside. When he later joins Akira in the carpark, he is sympathetic enough to give him 5000 yen, but as if to discourage similar requests for money in the future, he breaks off the conversation by insisting that he always used a condom when sleeping with Keiko and therefore, Yuki could not be his daughter. He also informs Akira of his own financial problems: a large credit card debt that he is struggling to clear. However, the reason for this debt – his girlfriend maxed out his cards shopping – demonstrates his failure to take seriously Akira’s far more perilous situation. Although it is left uncertain whether either man is Yuki’s father, they refuse to accept parental responsibility nonetheless, and Akira and his mother are treated as an inconvenience whose existence must be kept out of their lives.

Other, more sympathetic characters are likewise unable or unwilling to help Akira openly, or simply do not know how to help. A convenience worker who learns of the children’s predicament recommends to Akira that he should contact the police or child welfare, but he declines, hinting at an earlier episode involving such institutions which nearly split up the family. Another worker at the store helps Akira by donating expired food, but he must do so surreptitiously and by risking his own job, smuggling the goods out via a back entrance to the carpark. Later in the film, the children befriend Saki (Hanae Kan), a bullied middle-school girl who becomes somewhat of a love interest for Akira, and a surrogate mother and older sister for the children (it is she who sits opposite Akira in the opening scene). Although Saki is from a wealthy household, she is only able to offer moral and not material support. When Akira walks her home, he is not invited in and watches as she disappears behind the automatic security door of her building. Her family is clearly in a position to be able to help, but Saki never mentions the children to them (nor her family to the children) and instead schemes to raise money for Akira by accompanying an older man to karaoke – an act often considered to be a front for schoolgirl prostitution in Japan (Akira jealously refuses to accept her earnings despite her insistence that it was a platonic encounter). When the landlady visits to inquire about unpaid rent, she discovers Saki, and Akira’s half-siblings, sitting unsupervised in the filthy apartment. Despite the overwhelming signs that something is amiss, she appears to turn a blind eye, taking at face value Kyōko’s explanation that they are relatives of the family and that Keiko is away working in Osaka. Most of these characters have good intentions but none seem willing or able to disturb the social structures in which their lives are entrenched. “Nobody knows,” writes Adam Campbell in his review of the film, “because simply nobody wants to know.”[14] It would be equally accurate to suggest that everybody knows but nobody knows what to do.

These broader societal reflections ultimately remain muted, however, in favour of the film’s resolute focus on the children’s everyday experiences. As Koreeda explains, “my desire to understand these children was very strong, particularly their actions once they were left to their own devices.”[15] Primarily, Koreeda achieves this understanding through a carefully planned series of close-ups throughout the film which emphasises the children’s immediate actions and environment. Many of these close-ups exist as part of a conventional system of scene coverage – as insert shots or as fragments within a pattern of editing which also involves shots of other sizes – but they often constitute the very basis of the scene itself. For example, when Akira uses a return address on an envelope sent by his mother to track down her new phone number, Koreeda depicts his actions in an elliptical series of close-ups and extreme close-ups (while the sounds of the other children playing can be heard offscreen): Akira’s finger dialing a phone number, the address shown on the envelope, Akira’s face as he speaks to an operator, a phone number being written on a pad with a pencil, his finger dialing a new number, and so on. When Akira hears his mother’s voice on the other end of the line, introducing herself as “Yamamoto,” Koreeda holds on an extreme close-up of Akira’s lips, quivering and unable to speak. The next shot is a close-up from behind Akira’s head as he lowers the receiver, while the other children can be seen in the background, partially obscured and heavily out of focus.

Koreeda also creates an intricate series of close-ups that are detached from the immediate needs of the narrative. From the start of the film, the director instils everyday objects (suitcases, a pair of shoes, a toy piano, unwashed dishes, a bottle of nail polish) and actions (usually involving hands: washing potatoes, filling the bathtub, completing homework, turning on the kettle) with heightened significance, isolating them in ambiguous close-ups before their importance can be grasped. Some of these close-ups are repeated in different variations throughout the film and the associations made between them are relatively straightforward. For example, an early close-up of Kyōko’s hand pulling a cord and switching on the light anticipates the household electricity being cut off later in the narrative – an event which prompts its own close-up of Akira’s hand pulling the same cord in vain.

Other associations, however, are more complex. For example, Yuki’s death is prefigured by a network of images scattered throughout the film, including: a drop of red nail polish on the floor, which resembles the drop of blood next to Yuki’s body after she is killed; a pot plant plunging off the edge of the balcony, the location at which she falls from a chair; and several sets of tiptoeing feet, including Yuki’s, moments before her accident. Some of these close-ups also connect to other series of shots, and relate to other characters and themes. For example, Alexander Jacoby analyses in detail the “complex connotations” of the red nail polish throughout the narrative. He charts the symbolic trajectory of the object, which includes “Kyoko’s desire for maternal affection” when she first picks it up off her mother’s dressing table and inspects it; an item which “acquires foreboding symbolism” when Kyōko spills some on the floor; Keiko’s “desire to conceal the fissure at the heart of the family” when she tries to clean the spill; and eventually, when it is visible only as a red stain on the floor, it comes to evoke Keiko’s “absence and its long-term consequences for the family” as well as Kyōko’s “enduring attachment to her absent mother.”[16] Koreeda embeds many of these images in parallel to the main narrative; indeed, they usually function independently of it, and most of them could have been removed without affecting the unfolding story. But it is through their poetic associations – established across time and in fragments – that the children’s experiences are most strongly felt and understood.

Many of the filmed objects are recycled throughout the film – symbolically by Koreeda, literally by the children – after their initial functions are fulfilled. Just as Koreeda reuses imagery which gain new meanings across time, empty bowls of Cup Noodles are reused by the children as pots for seeds and then plants; unpaid bills turn into sketch pads; soft drink containers are refilled and used to carry water back from the park, after the utilities are disconnected; and most tragically, a suitcase, used to smuggle Yuki into the apartment at the beginning of the film, becomes a coffin, used to transport her body out of the apartment after her death. These isolated objects and gestures are what linger long after the film ends, reverberating as symbols of resilience, resourcefulness, misfortune, and dreams put on hold.

Koreeda applies a similar approach to locations shown throughout the film. For example, he repeatedly cuts to an unremarkable suburban intersection on which there is a vending machine, a payphone, some nondescript buildings and little else. This intersection will later be incorporated into the narrative (Akira uses the payphone after the home phone is disconnected) but more generally, it is simply a landmark that the characters walk past on their way to other parts of the neighborhood. However, through repetition and variation, Koreeda extracts from this banal location poetic effects that relate the children’s experiences. When Akira uses the payphone to call his mother at her workplace, he learns that she resigned a month earlier; it is the first sure sign that she will not be back. As he hangs up and walks away, Koreeda cuts out to an extreme wide-shot of the lifeless and colourless intersection, which assumes apocalyptic undertones and alludes to Akira’s despair. Later, Akira passes through the same intersection with his new friends (a group of schoolkids who eventually ditch him, after he refuses to partake in shoplifting), riding on the back of one of their bikes. This time it is dusk, streetlights dot the frame like stars, a family can be glimpsed through an apartment window, and Gontiti’s sprightly musical score accompanies the scene. The street corner becomes absorbed into a world of possibilities.

Elsewhere, Koreeda gets a lot of mileage from a shot of a dual outdoor staircase, the basic function of which is to act as a bridging shot between the apartment and other neighborhood locations. However, at various points in the film it is also used to connote freedom and adventure (when the four siblings dash up the stairs together for the first time); contrast the children’s lives to that of other children (Akira climbs it on his way to go shopping, while on the other side of the railing two kids sit on the steps and play); indicate a character’s triumph (when Akira descends with a bag of free food) or emotional hurdle (when he ascends with his mother to see her off for the last time); foreshadow an important encounter (Akira sees Saki for the first time when he reaches the bottom of the stairs, and Saki runs back up it); or simply to announce the change of season (the cherry blossom tree protrudes into the frame at the arrival of spring). The lyrical progression of everyday images and sounds parallels that of the children’s lives: as their money dwindles and their living conditions deteriorate, their universe paradoxically expands. Eventually, Akira takes liberties with the rules of the household and accompanies Yuki outside on her birthday; before long, the children come and go as they please. Outside the apartment, the children explore, discover sights and sounds, make and lose friends, and take new risks. That is to say, they learn, as all children learn.

At the end of the film, the children’s future, like that of Riichi in The Demon, remains uncertain: one of them has died, they are no less poor, and although they have found a valuable friend in Saki, they are still without a parent. Koreeda cuts again to the street corner described above, on a sunny summer’s day. Shigeru checks the coin return slot on the payphone, as he has become accustomed to do, and finds a coin for the first time. It is an unsubstantial amount but it registers as a triumph nonetheless, as he shouts his joy and runs to catch up with the rest of his family. It is through the repetition and progression of these small, everyday moments that Nobody Knows becomes a film in which the image of the child prevails as one of hope.

Conclusion

Child abandonment has been a recurring theme in postwar Japanese cinema and will likely remain so, as long as films correspond in some way to the realities they depict. Within this subset of films, The Demon and Nobody Knows address the theme of child abandonment directly, rather than allegorically, based as they are on horrific actual cases where allegory can offer no explanation nor route for escape. And remarkably, both films achieve the seemingly impossible feat of finding and emphasising hope in the image of the child, within narratives that do not seem to contain much hope to be shared.

Despite the innate bleakness of their narratives, both The Demon and Nobody Knows retain the optimistic spirit of many Japanese films about children. Even after his father attempts to murder him, the eldest child in The Demon refuses to blame him, displaying a level of compassion, maturity and empathy unseen in any of the adult characters. Nobody Knows ends on a quietly optimistic note as the children continue their lives as a makeshift family, having survived tragedy and stayed together. As such, Nomura and Koreeda successfully juggle two contrasting commitments: celebrating children in their own right, as individuals with agency, and using children to highlight the troubles of a world in which they are often the first to suffer the consequences. Both films are incisive critiques of Japanese society at a particular point in time, as well as studies of disturbing human behaviour that transcend the films’ historical and geographical settings. Above all, they are cinematic tributes to the resilience of children – one which, the films ultimately suggest, bodes well for the future.

Notes

[2] Akihisa Kouno and Charles F. Johnson, “Child Abuse and Neglect in Japan: Coin-Operated-Locker Babies,” Child Abuse & Neglect 19 (1995): 28.

[3] Jiji Press, “13 Infants Left in Kumamoto Baby Hatch in Fiscal 2015,” The Japan Times, July 20, 2016, accessed February 11, 2017, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/07/20/national/13-infants-left-in-kumamoto-baby-hatch-in-fiscal-2015/#.WPbGFVOGNE4.

[4] Kyodo News, “Nearly 400 Children Abandoned in Japan Since 2011: Survey,” The Japan Times, July 20, 2014, accessed December 1, 2016, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/07/20/national/social-issues/nearly-400-children-abandoned-in-japan-since-2011-survey/.

[5] Vicky LeBeau, Childhood and Cinema (London: Reaktion Books, 2008), 141.

[6] Hiroshi Wagatsuma, “Child Abandonment and Infanticide: A Japanese Case,” in Child Abuse and Neglect: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, ed. Jill E. Korbin (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981), 101.

[7] Roman Rosenbaum, “Reading Shōwa History Through Manga: Astro Boy as the Avatar of Postwar Japanese Culture,” in Manga and the Representation of Japanese History, ed. Roman Rosenbaum (New York: Routledge, 2013), 45.

[8] Alexander Jacoby, “Why Nobody Knows – Family and Society in Japan,” Film Criticism 35 (2011): 74.

[9] Helen Hardacre, Marketing the Menacing Fetus in Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 44.

[10] Karen Lury, The Child in Film: Tears, Fears and Fairytales (London: I.B. Tauris, 2010), 74.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Film critic Akira Iwasaki describes “Ozu’s reasoning [for this shot] as follows: the Japanese people spend their lives seated on ‘tatami’ mattings spread over the floor; to attempt to view such a life through a camera high on a tripod is irrational; the eye-level of the Japanese squatting on the ‘tatami’ becomes, of necessity, the level for all who are to view what goes on around them; therefore, the eye of the camera must be at this level.” See Roy Huss and Norman Silverstein, The Film Experience: Elements of Motion Picture Art (New York: Delta, 1968), 112.

[13] Phil Hoad, “The Demon – The Film That Breaks the Last Cinematic Taboo,” The Guardian, April 18, 2014, accessed November 4, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/apr/18/the-demon-yoshitaro-nomura-child-abuse.

[14] Adam Campbell, “Nobody Knows,” Midnight Eye, November 22, 2005, accessed January 22, 2017, http://www.midnighteye.com/reviews/nobody-knows/.

[15] Kuriko Sato, “Hirokazu Kore-eda,” Midnight Eye, June 28, 2004, accessed January 22, 2017, http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/hirokazu-kore-eda/.

[16] Jacoby, “Why Nobody Knows,” 67–68.

Bibliography

Anderson, Joseph L., and Donald Richie. The Japanese Film: Art and Industry. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982.

Campbell, Adam. “Nobody Knows.” Midnight Eye, November 22, 2005. Accessed January 22, 2017. http://www.midnighteye.com/reviews/nobody-knows/.

Hardacre, Helen. Marketing the Menacing Fetus in Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Hoad, Phil. “The Demon – The Film That Breaks the Last Cinematic Taboo,” The Guardian, April 18, 2010. Accessed 4 November, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/apr/18/the-demon-yoshitaro-nomura-child-abuse.

Huss, Roy, and Norman Silverstein. The Film Experience: Elements of Motion Picture Art. New York: Delta, 1968.

Jacoby, Alexander. “Why Nobody Knows – Family and Society in Japan.” Film Criticism 35 (2011): 66–83.

Jiji Press. “13 Infants Left in Kumamoto Baby Hatch in Fiscal 2015.” The Japan Times, July 20, 2016. Accessed February 11, 2017. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/07/20/national/13-infants-left-in-kumamoto-baby-hatch-in-fiscal-2015/#.WPbGFVOGNE4.

Kouno, Akihisa, and Charles F. Johnson. "Child Abuse and Neglect in Japan: Coin-Operated-Locker Babies." Child Abuse and Neglect 19 (1995): 25–31.

Kyodo News. “Nearly 400 Children Abandoned in Japan Since 2011: Survey.” The Japan Times, July 20, 2014. Accessed December 1, 2016. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/07/20/national/social-issues/nearly-400-children-abandoned-in-japan-since-2011-survey/.

LeBeau, Vicky. Childhood and Cinema. London: Reaktion Books, 2008.

Lury, Karen. The Child in Film: Tears, Fears and Fairytales. London: I.B. Tauris, 2010.

Rosenbaum, Roman. “Reading Shōwa History Through Manga: Astro Boy as the Avatar of Postwar Japanese Culture.” In Manga and the Representation of Japanese History, edited by Roman Rosenbaum, 40–59. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Sato, Kuriko. “Hirokazu Kore-eda.” Midnight Eye, June 28, 2004. Accessed January 22, 2017. http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/hirokazu-kore-eda/.

Wagatsuma, Hiroshi. “Child Abandonment and Infanticide: A Japanese Case.” In Child Abuse and Neglect: Cross-Cultural Perspectives, edited by Jill E. Korbin, 120–138. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981.