Legacy of a Law-breaker: Andrew Dominik’s Chopper Turns Twenty

Originally published in Metro no. 203 (January 2020).

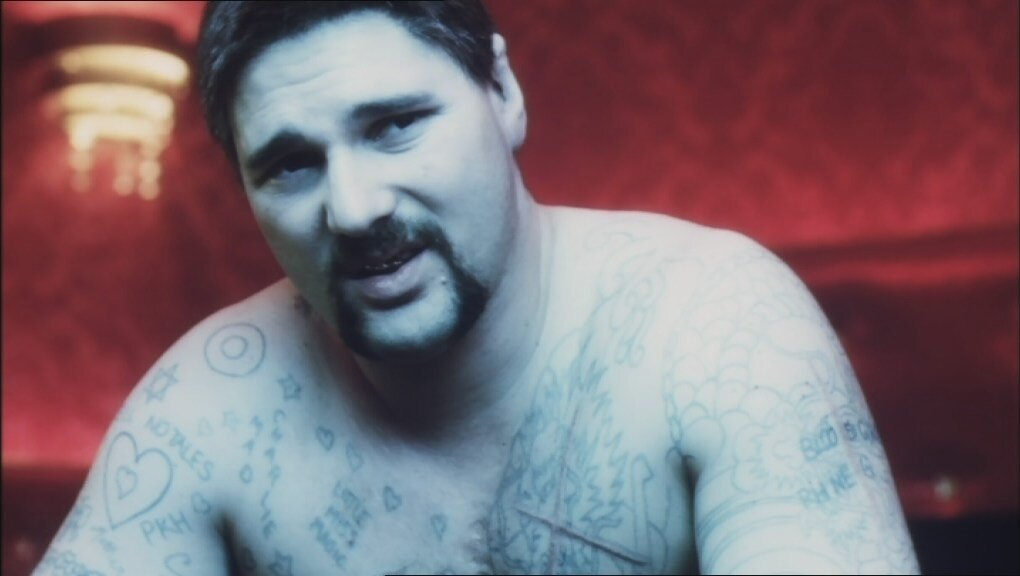

‘So often, in movies, violent characters are portrayed as [...] supernaturally evil or there’s [... an] ideological justification for everything they do,’ suggested director Andrew Dominik prior to the release of Chopper (2000), his debut film about the notorious Australian criminal Mark ‘Chopper’ Read. ‘I just wanted him to be a human being – sort of demystify him, in a way.’[1] Chopper’s Chopper (Eric Bana) is a violent character, to be sure, but he isn’t supernaturally evil, nor does the narrative give any ideological justification for his actions. On the whole, he’s portrayed as very much human: full of contradictions and hang-ups, some more convincing than others.

But is he demystified? It’s difficult to take Dominik at his word when we see Chopper rooted in place as he’s stabbed half a dozen times by his prison-mate Jimmy (Simon Lyndon), showing no trace of pain or fear on his terrifyingly stoic face. ‘What’s gotten into you?’ he asks after the third plunge of the knife into his belly, as if to a misbehaving pet dog; then, following a fourth stab, he offers his anxious assailant a hug. When Chopper eventually lies weakened from his wounds, it feels like a detail included begrudgingly – not out of any respect for reality (Read lost part of his bowel and several feet of intestine from the incident[2]), but only to prevent the film from tipping over into fantasy. The scene practically renders its protagonist superhuman, elevating him alongside those awe-inspiring screen villains who just can’t seem to be killed – an ocker and more down-to-earth Michael Myers, Terminator or Anton Chigurh.[3] No, Read isn’t demystified; Chopper makes its titular criminal’s myth visible and palpable.Dominik can be forgiven for spinning his own intentions. He’d been stuck in production limbo for seven years,[4] somehow struggling to convince investors that there was an appetite for a film about a celebrity criminal who’d had his own ears amputated and claimed to have been involved in the murder of nineteen people (later downgrading the tally to ‘about four or seven, depending on how you look at it’, a few months before his death).[5] The film also came at a time when conservative politicians, Christian lobby groups and the Office of Film and Literature Classification (now the Australian Classification Board), under the watchful eye of John Howard’s government, were particularly keen to make their mark on the nation’s film culture; its release was sandwiched between a spate of controversial works that were banned, or came close to being banned, like Lolita (Adrian Lyne, 1997), Romance (Catherine Breillat, 1999), Baise-moi (Virginie Despentes & Coralie Trinh Thi, 2000), Irreversible (Gaspar Noé, 2002) and Ken Park (Larry Clark & Ed Lachman, 2002).[6]

Chopper predictably drew controversy from those fearing the glorification of a violent criminal and the violence that a film about such a criminal would entail. But they needn’t have been so worried. Although it features a couple of disturbing scenes, Dominik’s film was no more or less violent than countless others of its kind, and its violence feels even less remarkable today. Moreover, glorifying criminals – or, perhaps, allowing the public to watch, enjoy and try to understand fictionalised versions of them – had long been a cinematic staple, albeit, oddly, a hitherto-underrepresented one for a nation as obsessed with crime as Australia. ‘Those who earnestly question the ethics and morality of a project like Chopper’, wrote critic Adrian Martin in his contemporaneous review of the film, ‘have obviously not kept abreast of popular cinema for the past thirty years.’[7]

And if there were ever a cinematic work that ought to have been shielded from such accusations, Chopper was it. Nothing it contained could compare to the self-glorification that Read himself had already sought and attained through his bestselling memoirs, the material on which Dominik’s film is based. It was provided further immunity by the fact that Read’s testimonies had become infamous for their unreliability (‘Endlessly repeated but never consistent, vivid but lacking in credible detail, possible but implausible, or plausible but impossible’,[8] according to the co-author of his final autobiographical work) and flippant attitude towards truth (‘This book is based on a true story, which means some of it is rubbish’,[9] reads the author’s note of the same text). None of this, of course, is to deny the film’s contribution to spreading Read’s notoriety. After Chopper's success, Read embarked on stand-up comedy tours around the country, wrote more books, exhibited paintings and produced a hip-hop album,[10] not to mention appearing in commercials[11] and being profiled in the international press;[12] following his death in 2013, he even received an entry in the Underbelly franchise[13] – and on and on it goes.

So what is Chopper? It’s a biopic that doesn’t feel like one, focusing, as it does, on a fairly narrow chunk of its subject’s life: the narrative spans from 1978 to 1992, covering a portion of two separate prison stints and a brief period of freedom in between. It’s a film that both questions the mythologisation of Read – it’s bookended with Chopper admiring his own media performance on TV, and a key sequence contrasts different versions of his killing of Siam ‘Sammy the Turk’ Ozerkam (Serge Liistro) – and complements it with fanciful filmic interpretations and embellishments. Like many notable genre titles, Chopper relies heavily on archetypes and establishes its own. It’s a ‘gangster film’ by virtue of the familiar iconography it uses (guns, drugs, nightclubs, sexy women), but, for the audience, the word ‘gangster’ may not apply naturally to criminals like Read, even though he did, in fact, head a couple of gangs. Gangsters, according to the popular imagination (following the influence of classic works like Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 The Godfather), partake in slick, organised crime. They’re members of Italy’s mafia, China’s triads, Japan’s yakuza, Mexico’s cartels – not buffoons whose ‘business’ is conducted over beers in drab lounge rooms and tacky nightclubs, and whose associates form part of a loose network of low-key crooks and junkies. This shambolic quality is best exemplified by a sequence in which Chopper shoots drug dealer Neville Bartos (Vince Colosimo) in his home, then drives him to hospital in virtually the same motion; this world of crime is memorable precisely because it’s so disorganised.

In showcasing such incongruity, however, Chopper refreshed the iconography of the Australian crime genre. In the film, ‘crime doesn’t pay’ isn’t just a moral but a literal and visible fact. It’s there in plain sight, in the shitty, low-rent houses and apartments; in the utter lack of distinction between domestic and criminal spaces; and in the gangsters who talk and act tough, but whose financial situations range from modest to flat broke. This unglamorous world is accentuated by Geoffrey Hall’s and Kevin Hayward’s cinematography,[14] which lights rooms like reptile tanks and uses a bleach bypass to reduce the palette to a couple of grimy colours per scene. Yet, despite its distinctive visual design, Chopper has an undeniably cheap and unfussy look – a side effect of the film’s budgetary limitations – and Dominik has explained how he often downplayed stylistic considerations during the shoot so he could concentrate on the performances.[15] Several Australian crime films would go on to adopt elements of Chopper’s grubby visual template – from Brett Leonard’s Feed (2005) to Serhat Caradee’s Cedar Boys (2009) to Ben Young’s Hounds of Love (2016) – but no other screen work quite achieved its peculiar look and mood.

The most memorable and influential element of the film is Chopper himself. Bana’s grotesque portrayal of simultaneous charm and menace, hovering perpetually between benign larrikin and compulsive psychopath, resonates in the characterisations of myriad criminals of all stripes in subsequent Australian films: John Jarratt’s Mick Taylor in Wolf Creek (Greg McLean, 2005), Ben Mendelsohn’s Pope and Jacki Weaver’s Smurf in Animal Kingdom (David Michôd, 2010), and Daniel Henshall’s John Bunting in Snowtown (Justin Kurzel, 2011).[16] While cinema history has seen many villains, psychopaths and antiheroes who possess such sharply contrasting qualities, it was Bana who opened the floodgates in the local arena and cemented these qualities as iconic traits of the Australian screen criminal.

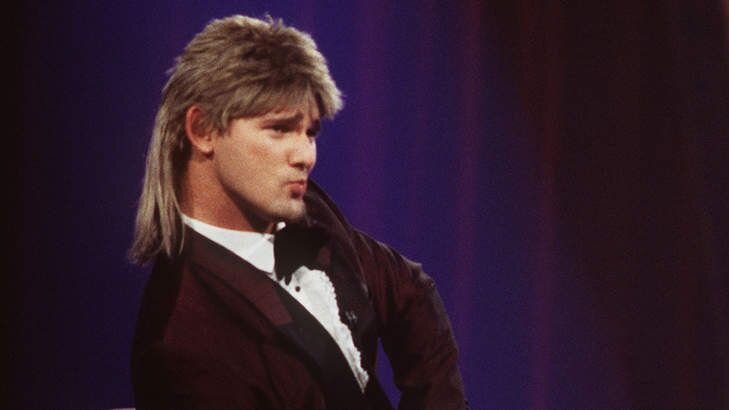

Some critics at the time felt compelled to compare Chopper to its Hollywood counterparts,[17] but it was never playing the same game as them. The stakes of its plot are so low, its look and mood so detached from realism, and the protagonist so sheltered from consequence or conventional psychology that the film becomes freed up to be appreciated as a series of skits or set pieces centred on Bana’s volatile performance. Consequently, the film is always less interesting for what Chopper says and does, and more for how he says and does it. It’s replete with eccentric gestures, cadences of speech and turns of phrase (‘Beethoven had his critics, too, Keith – see if you can name three of them’; ‘If you wanna be like your Uncle Chop-Chop, get them bloody ears off’) that nevertheless always feel organic to the character and context. Bana’s rendition of Chopper lies at the perfect intersection between comedy and drama, which aptly came during a crossroads in his career as he transitioned from Australian comic to international screen dramatist. Yet it’s much closer in spirit to his virtuosic roles on the 1990s skit show Full Frontal – apparently what prompted Read to suggest Bana as a lead in the first place[18] – than anything he did afterwards.

Chopper won big at the Australian Film Institute’s awards[19] and propelled its star and director to the ranks of Hollywood, where they went on to make bigger, but not necessarily better, things. Hollywood still doesn’t know what to do with Bana. Barely any of the high-profile directors he has worked with have taken advantage (or have even seemed aware) of his comedic abilities, and he has never looked, sounded or felt quite right in the straitlaced films he has appeared in. Dominik has directed some solid films while maintaining the glacial working pace established at the start of his career. His fascination with criminal mythology continued with The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007), which came out seven years after Chopper; it was followed by the contemporary crime drama Killing Them Softly (2012), then the Nick Cave documentary One More Time with Feeling (2016). Although he recently resurfaced as director for a couple of episodes of Netflix’s Mindhunter, Dominik still seems to be troubled by development problems for his feature projects. Plans to direct Cities of the Plain, an adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s eponymous novel, and War Party, an adventure film starring Tom Hardy, appear to have collapsed. However, a biopic about Marilyn Monroe first hinted at a decade ago is finally slated to be produced for Netflix.[20]

Twenty years after its release, Chopper remains Bana’s best performance and Dominik’s best film. It has aged well, although probably not in the way its makers would’ve foreseen. Next to the Australian crime films that followed in its wake, many of which significantly upped the ante for violence and depravity, Chopper now seems rather innocuous – more unusual than it is hard-hitting. Perhaps this is in keeping with Read himself: a man whose image gradually softened until his death from liver cancer; a man who boasted about horrible deeds, but who somehow always managed to remain likeable, even loveable. Whatever one makes of him, the film that bears his nickname has carved out a permanent place in Australian cinema history – and has allowed many others to crawl in alongside it.

Endnotes

[2] Garth Cartwright, ‘Mark “Chopper” Read Obituary’, The Guardian, 9 October 2013, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/oct/09/mark-chopper-read-obituary>, accessed 16 October 2019.

[3] Key antagonists in the Halloween franchise, the Terminator films and No Country for Old Men (The Coen brothers, 2007), respectively. The first two are played by various actors, and the third, by Javier Bardem.

[4] See Laura Carroll, ‘Chopper, or Adventures in the Standover Trade’, Metro, no. 124/125, 2000, p. 90; and Andrew Dominik, ‘Chopper’, in Raffaele Caputo & Geoff Burton (eds), Third Take: Australian Film-makers Talk, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2002, pp. 70–71.

[5] Mark ‘Chopper’ Read, quoted in Matt Siegel, ‘Australia’s Brand Name for Ferocity, Softened by Time’, The New York Times, 12 April 2013, <https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/13/world/asia/chopper-read-australias-brand-name-for-ferocity-is-softened-by-illness.html>, accessed 16 October 2019.

[6] See Jim Schembri, ‘Censors and Sensibilities’, The Age, 13 February 2004, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/movies/censors-and-sensibilities-20040213-gdxaq1.html>, accessed 16 October 2019.

[7] Adrian Martin, 'Chopper', Film Critic: Adrian Martin, August 2000, <http://www.filmcritic.com.au/reviews/c/chopper.html> accessed 16 October 2019.

[8] Simone Ubaldi, ‘The Making of “Chopper” Read’, The Monthly, November 2013, <https://www.themonthly.com.au/issue/2013/november/1383224400/simone-ubaldi/making-chopper-read>, accessed 16 October 2019.

[9] Mark ‘Chopper’ Read & Simone Ubaldi, Road to Nowhere, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2011, p. v.

[10] See ‘Everything You Need to Know About Mark “Chopper” Read’, Herald Sun, 2 February 2018, <https://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/everything-you-need-to-know-about-mark-chopper-read/news-story/9bae9a3545b95fa4f071c18b20b77520>, accessed 16 October 2019.

[11] See, for example, ‘Chopper – Anti Violence to Women Advertisement’, YouTube, 17 July 2006, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g_2M3LrfFAw>, accessed 16 October 2019.

[12] See, for example, Siegel, op. cit.

[13] The Nine Network’s Underbelly Files: Chopper, which aired in February 2018.

[14] Hayward replaced Hall halfway through the project; see Dominik, ‘Chopper’, op. cit., p. 200 (endnote 5).

[15] See Matt Quill, ‘Chopper: The Inside Job – an Interview with Andrew Dominik’, Metro, no. 124/125, 2000, p. 97; and Dominik, ‘Chopper’, ibid., p. 73.

[16] Arguably, it’s a non-Australian crime film, however, that owes the biggest debt to Chopper’s tone and lead performance: Nicolas Winding Refn’s Bronson (2008), about Britain’s closest criminal equivalent to Read, Michael Peterson.

[17] See, for example, Martin, op. cit.; and Jeff Vice, ‘Film Review: Chopper’, Deseret News, 18 May 2001, <https://www.deseret.com/2001/5/18/20089711/film-review-chopper>, accessed 16 October 2019.

[18] See Kevin West, ‘Eric Bana’, W magazine, 1 August 2009, <https://www.wmagazine.com/story/eric-bana>, accessed 16 October 2019.

[19] It won the AFI Awards for Best Direction, Best Lead Actor and Best Supporting Actor, and received seven other nominations.

[20] See Scott Wampler, ‘Andrew Dominik’s Blonde May Have Found Its Marilyn Monroe’, Birth.Movies.Death., 15 March 2019, <https://birthmoviesdeath.com/2019/03/15/andrew-dominiks-blonde-may-have-found-its-marilyn-monroe>, accessed 16 October 2019.