Pass it on: Mysterious Object at Noon

An annotation for The Melbourne Cinémathèque’s ‘Drifting States: The Films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’ programme, initially scheduled to run at ACMI from 23 June to 7 July 2020 before being cancelled because of you-know-what. Also published (without a star rating) in Senses of Cinema Issue 94 (April 2020).

Mysterious Object at Noon (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2000)

★★★★★

Mysterious Object at Noon. Even at a first glance, Thai artist and filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s first feature has one of the most evocative titles in the history of cinema (the original title, Dogfahr nai meu marn, which translates as “Dogfahr in the Devil’s Hand,” decidedly less so). What could this “mysterious object” refer to? Is it something familiar that turns mysterious when the clock strikes 12, or something mysterious to begin with? Whatever it is, the object is seen, incongruously, at noon, that unmysterious time of day when everything is plain and visible. Can an object at noon be that mysterious?

True to its name, Mysterious Object at Noon (2000) is a work in which the vague and the specific, and the enigmatic and the mundane, rub shoulders at every stage. The film begins, as far as we can tell, in firmly documentary territory, observing a mobile seafood vendor selling merchandise in the Bangkok suburbs. During a lull in business, one of the workers recounts a tearful anecdote from the back of the truck. As a child, her parents sold her into servitude so that they could afford bus tickets home. Weerasethakul’s offscreen voice then asks her, abruptly and rather insensitively, if she has “any other stories to tell us,” whether real or fictional. She collects her thoughts, then begins to narrate the first lines of a story about a boy in a wheelchair, sealed from the outside world, and his home-school teacher, a woman named Dogfahr.

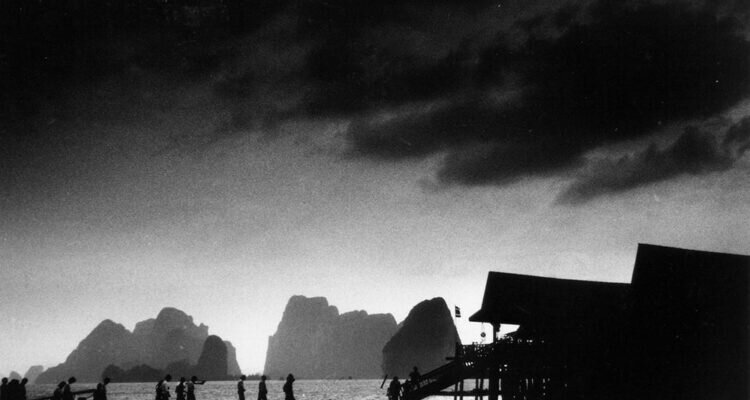

These initial words became the jumping-off point for both the film and the filmmaker. Over two years, Weerasethakul and his small crew travelled through Thailand (following an urban-to-rural trajectory seen in several of his films) inviting locals to contribute to the story by adding, in their own words and in their own way, a section to it before passing it on for the next person or people to do likewise. The conceit is broadly familiar; it’s a cinematic equivalent of cadavre exquis (“exquisite corpse”), the Surrealist game wherein an artist completes a portion of a drawing then hands it to another artist to be continued. In Weerasethakul’s experiment, the pen is replaced with a camera and microphone, paper with black-and-white 16mm film (later blown up to 35mm), and drawing with whatever method of storytelling the participants saw fit (impromptu interviews, musical performance, sign language). The chain of storytellers, which could have conceivably continued forever, is comprised of a cross-section of Thai working-class society that spans various ages, regions and ethnicities – and include an elderly orange farmer, a group of young elephant herders and a huddle of schoolchildren who jostle for the camera’s attention as they try to take the reins of the story. In their collective hands, the narrative zigzags to encompass shapeshifting characters, a neighbourhood romance, local superstitions, a wartime flashback and multiple incarnations of objects both mysterious and not.

Mysterious Object at Noon is the result and the record of this curious collaboration, in which the story and its telling always go hand in hand. After the bulk of the shooting had wrapped, Weerasethakul filmed an enactment using nonprofessional actors – adding his own variations and embellishments in the process – which is used to visualise parts of the story as it is narrated. As this story twists and turns, documentary segments detail the crew’s journey and their process of making the film at that point in time. Interactions between the filmmakers and the participants are recorded, occasional detours are taken to observe villagers’ everyday lives, and one local’s complaint about the lack of a screenplay is duly noted. The shifts between fiction and documentary aren’t easy to identify, which can make the film difficult to follow at first. The shooting and editing style rarely deviates to suggest one or the other – the dramatisations tend to be filmed in a more controlled manner, but not necessarily so – and visually speaking, the cinematography homogenises the different planes of reality in its grainy indistinctness. The usual signposts are absent; when they’re there, they’re often unreliable. Intertitles punctuate fictional and documentary sequences alike, and in the dramatisations, which are sometimes filmed in real locations and amongst real people, different actors play the same roles as the tale progresses. Even a seemingly straightforward fictional or documentary sequence may not turn out to be that at all. Sounds heard in the documentary segments are regularly carried over to the dramatisations, and vice versa; actuality footage may be deployed in a fictional context, and vice versa. The result is a sometimes confusing but always absorbing experience in which documentary and fiction, reality and fantasy, the outcome and the process, are often conveyed by the filmmaker – and perceived by the viewer – at the same time.

This structure may come across as overwrought to viewers unaccustomed to such fluid distinctions of reality, just as the story itself might seem frivolous to those whose cultures afford little significance to superstition and the uncanny (the film engages with such elements in a spirit of playfulness, but no less sincerely, and the same can be said for much of Weerasethakul’s oeuvre). Given where the film goes and how it goes there, it’s also easy to forget that the story first emerges in the wake of something very real – as an apparent response that might illuminate, or offer temporary refuge from, an individual’s traumatic past of poverty and abandonment. What follows thereafter, however, doesn’t merely advocate stories as escapism from social reality; indeed, the woman’s past is also conveyed in the form of a story, and we’re never told to what extent her subsequent story might be real or imagined. Such questions may be beside the point. The film goes on to humbly show how stories and storytelling are every bit as part of social reality as work and play, languages and customs, cities and villages – as concrete expressions of social reality rather than as distinct from it.

In this manner, Mysterious Object at Noon celebrates the very act of storytelling as it is practised in everyday life, individually and collectively, for reasons both profound and banal. Along the way, it also chronicles a fascinating culture in which fantasy and reality don’t collide but coexist, one shaping the other in ways that will always remain elusive. At the end, in a mysterious coda, the film seems to revert back to the stable and recognisable reality in which it began, as it matter-of-factly observes a crowd of children playing in a village at noon. But by this stage, this quotidian world has morphed into a film set of endless possibilities, ready to be passed on and remoulded by anyone who wishes.