Riot and Revenge: Symmetry and the Cronulla Riot in Abe Forsythe’s Down Under

Originally published in Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Issue 13 (Summer 2017), edited by Loretta Goff and Caroline V. Schroeter.

Introduction

During the first week of December 2005, news of an incident on Cronulla Beach spread throughout Sydney: three white off-duty lifesavers had been involved in an altercation with four young men of Lebanese background and were bashed. Within the Sutherland Shire—known colloquially as “The Shire”, a predominantly Anglo area of southern Sydney which includes Cronulla Beach—a sense of communal outrage gained momentum as news, rumours and misinformation about the incident circulated. Although a report overseen by former New South Wales Assistant Police Commissioner Norm Hazzard would later conclude that the event was minor and “not of any greater significance than other events around the same time involving Middle Eastern and Caucasian Australians” (Strike Force Neil 7), it received widespread attention in the commercial media, particularly on talkback radio where many callers piggybacked complaints of Middle Eastern youths who had allegedly been displaying antisocial behaviour towards beachgoers for years. During the same week, thousands of SMS messages were disseminated, inciting a call to arms: “This Sunday every Fucking Aussie in the shire, get down to North Cronulla to help support Leb and wog[1] bashing day . . . Bring your mates down and let’s show them this is our beach and they’re never welcome back” (“Riot and Revenge”). Sydney’s daily tabloid The Daily Telegraph reprinted the message in full, and on his hugely popular radio show on 2GB, Alan Jones read out the entire message, word for word, half a dozen times during the week (Marr 61).[2]

On Sunday 11 December, over 5000 white Australians responded to the call and descended on Cronulla. In the morning, they cooked BBQs and drank beers in a festive atmosphere resembling Australia Day celebrations held annually throughout the country. By the early afternoon, despite the police and media presence, they had turned into a vicious mob, harassing, chasing and bashing anybody who they perceived to be of Middle Eastern appearance. Many were draped in the national flag and sported racist slogans (“Fuck Off Lebs”, “We Grew Here, You Flew Here”), proudly displayed their white bodies, and chanted their claims of ownership of the beach and the nation. A spate of violent retaliatory attacks and property damage occurred over the following nights, as community leaders called for calm and restraint. The horrific events at Cronulla and their aftermath brought Australia’s simmering racial tensions out into the open, and would have a profound impact on how race relations in the nation are discussed and understood. As the Hazzard report ominously put it, these events “carried with them a clear message to the Australian community that our multicultural society has now entered a new phase of its development” (Strike Force Neil 6).

Figure 1: A man is surrounded and bashed at Cronulla Beach on Sunday 11 December 2005. Andrew Meares/Fairfax 2005.

Eleven years on, an Australian feature film has based its narrative around what has come to be known as the Cronulla riot.[3] Abe Forsythe’s black comedy Down Under (2016) begins with a caption of the abovementioned text message, set against a black screen. Paired ironically with the strains of “We Wish You a Merry Christmas”, a montage of documentary footage from Cronulla follows, depicting what appeared initially to be a collective display of national pride escalating rapidly to racial mob violence. As it turns out, the riot provides not the immediate focus but rather the prologue for the film that comes next. The narrative of Down Under begins on the day after the riot and depicts the parallel paths of a group of four young Anglo-Australian men from the Shire who wish to “protect” their turf, and a corresponding group of four young Lebanese-Australian men from the western suburbs seeking revenge for the events of the previous day. The film cuts back and forth between these groups—depicted as equally stupid and incompetent, and both driven by ignorance and macho aggression—as they gather crew and weapons, speed around in their cars, and search for a target upon which to direct their rage. Both groups begin with a sporting instrument for a weapon (a baseball bat and a cricket bat, respectively), then visit eccentric acquaintances from whom they acquire a firearm (a First World War rifle containing one bullet, and a handgun). After a series of detours and interludes, the two groups inevitably collide and the film climaxes in a spectacular scene of violence where it all began: at the beach.

As this brief description of the film may already suggest, a dominant trait of Down Under is that it pays equal attention, in its allocation of screen time and in its narrative and formal emphases, to the opposing sides of the racial divide that became pronounced during the Cronulla riot and its aftermath. In her review of the film, Amal Awad describes the narrative as being based around “a single night that depicts the rage on both sides: the Aussies defending their beach, and the Lebanese guys fighting back. Two cars loaded with testosterone, fear and hate—they mirror each other”(emphasis added). It is this process of “mirroring”—a calculated and balanced symmetry of representation—which is the film’s most distinctive quality and which gives it its central shape and meaning.

For the most part, the strongest articulations of symmetry in Down Under are structural and not aesthetic. Symmetry is barely integrated into the visual design of the film, unlike, for example, the recurring symmetrical compositions in works by filmmakers such as Chantal Akerman, Wes Anderson, Peter Greenaway and Stanley Kubrick, where symmetry “implies balance through a rigid ordering of the picture plane” (Kolker 65). For this reason, notions of symmetry usually applied to the visual arts—for example, the geometric forms theorised by Hermann Weyl in Symmetry (1952)—are mostly inapplicable. But as I.C. McManus suggests, symmetry does not “have to be visual or spatial: music with the A-B-A structure of sonata form, a play with its balanced structure of beginning, middle, and end, the Doppler shift as a whistling train screams by, the lists could be endless” (158). Above all else, Down Under creates a lasting impression of symmetry which can be gauged by considering the film’s structure and the narrative and formal elements that sustain its balance. Rudolf Arnheim asserts that “[s]ymmetry derives ultimately from a state of equilibrium” (285); it is the myriad ways in which Forsythe’s film achieves a state of structural equilibrium throughout its narrative, and the subsequent effects of doing so, which is the concern of this article.

Writing just months after the riot, Suvendrini Perera identifies a symmetrical narrative of “riot and revenge” which had emerged, where “race terror on the beach at Cronulla becomes explicable only retrospectively, in light of what followed it” (emphasis in original). Cronulla Beach, she goes on, “comes to stand for a paired sequence of events, the riot and the revenge, in a fable of equivalence in which two misguided groups, mostly of young men, mirror each other’s ignorance and prejudices”. As it happens, Down Under’s central symmetry resembles that of the “riot and revenge” narrative, presenting a version of events which links the racial violence at Cronulla and the subsequent retaliatory attacks as a symmetrical sequence. More crucially, the two events and the characters that represent them are presented as proportional in their impact and significance, thereby negating each other.

Figure 4: The Shire group (from left to right): Shit Stick, Evan, Jason and Ditch. Down Under. Studio Canal, 2016

Figure 3: The western suburbs group (from left to right): Hassim, Nick, Ibrahim and D-Mac. Down Under. Studio Canal, 2016.

This symmetry can be conceptualised as a counterbalance scale, with the Anglo-Australian group from the Shire on one side and the Lebanese-Australian group from the western suburbs on the other. When either group demonstrates positive or negative qualities within the narrative, the scale tips, but the opposite group will subsequently demonstrate a corresponding quality that restores equilibrium. Concurrently, Forsythe creates a succession of smaller, formal symmetries and rhymes—on the film’s soundtrack, via its cinematography and editing patterns, and extending to the visual design of the marketing materials—that reinforces this structural balance, as well as producing its own set of equivalences that function independently of the narrative. This process repeats throughout the film in a seesawing series of balancing equivalences that eventually collapses different issues, contexts and articulations of prejudice into an indistinguishable whole—simply presenting each group as equally good and bad.

Despite the film’s antiracist sentiments, its insistence on upholding this symmetry ultimately obscures the causes and significance of the riot, and dilutes the issue of race. It is a strategy which weakens the film’s antiracist stance, and aligns it unwittingly with the views of those who downplayed racism as a factor in the Cronulla riot and, worse yet, with proponents of the riot who denied racism outright and attempted to deflect blame back to the victims themselves. As such, it becomes easy to lose sight of the key context, and the apparent subject, of the film: the racism underlying the Cronulla riot. The traits, behaviours and actions of both groups of characters are afforded parity on a narrative and formal level, within a general paradigm of masculine aggression that becomes distanced from race.

Riot and Revenge

In outlining the symmetrical narrative that emerged after the Cronulla riot, Perera takes her cue from the ABC’s (Australian Broadcast Corporation) Four Corners report titled “Riot and Revenge”, which was first broadcast in March 2006 and was presented by the national broadcaster as “the definitive account of the riot at Cronulla and its aftermath”. Predictably, it is a report whose structure reflects the paired sequencing of events that Perera describes, focusing on the beach riot in the first half and the retaliatory attacks in the second half. Although the report provides valuable insight into why people from both sides participated (or refused to participate) in violence, it ultimately places equal emphasis on the two groups and the manner in which, in Perera’s words, they “mirror each other’s ignorance and prejudices”. Other journalistic pieces and documentaries about the Cronulla riot vary in quality and scope, but many narrate the events using a similar structure, airing the grievances and emphasising, if not always balancing, the wrongdoings of both sides of the conflict. In other words, the beach riot and the reprisal attacks have become inseparable, and this perhaps explains why they are often taken together and pluralised as the Cronulla “riots”.

A far more problematic articulation of this symmetrical narrative can be found in David Burchell’s article published in The Australian newspaper on Australia Day 2006, in which he frames the riot in direct relation to “a volley of equally violent and damaging revenge attacks” on the following nights. “And ethnic dislike (against ‘Aussies’ and, by a strange extension, the flag)”, he continues, “was just as obvious in these attacks as in their predecessors” (12). Perera responds to Burchell’s “reassurance in the fable of symmetrical hatreds” by asking:

How to convey to Burchell that the singling out for attack of “individuals of even vaguely Middle-Eastern appearance” by those “Aussies” sporting the flag as a sign of birthright and (ethnic) loyalty to British stock may have had something to do with the “strange” display of “ethnic dislike” that followed it? How to insert into the symmetrical narrative of riot and revenge the ways in which “individuals of even vaguely Middle-Eastern appearance” have been systematically excluded . . . from the space of the “homeland” designated by this same flag? . . . Ignoring these exclusions, the fable of equivalent “ethnic dislikes”, positions the violence of Cronulla Beach as a set of paired aversions that cancel one another out.

The danger in claiming equivalence between these two events, therefore, is not only that it places a massive, premeditated and racially motivated riot on equal footing with a series of smaller, spontaneous and retaliatory acts of violence. It structures as equal two groups whose place and position of power within Australian society are far from equal, and obscures the vastly different contexts in which the two sets of violence were carried out. Furthermore, it downplays or even eliminates the overt racism underlying the riot by linking the separate events as reciprocal acts of criminality (for Burchell, also reciprocal displays of “ethnic dislike”) that neutralise each other—and this disavowal of racism, Perera argues, “can in turn be located within a wider denial of the continuing role of race in contemporary Australia.”

Various politicians, conservative columnists and other public figures were quick to claim such equivalence between the riot and the reprisal attacks. Many went further, denying outright the role of racism in the beach riot and shifting the blame back to Lebanese-Australians (or Arabs, Muslims or Middle Eastern people, the distinction between which had already become eroded). In The Australian, Paul Kelly dismissed the rioters as a minority of “white supremacist cells” (12), while in The Sydney Morning Herald, Miranda Devine hyperbolically referred to the reprisal attacks as “Sydney’s mini Kristallnacht ‘night of broken glass’”. Perhaps the most damaging example was the notorious refusal of then Prime Minister John Howard to accept racism as a factor in the riot. “I do not accept there is underlying racism in the country”, he declared to the press on the day after. “I think yesterday was fuelled by the always explosive combination of a large number of people at the weekend and a large amount of alcohol.” In a perverse reframing of the riot which implied that it may have been an inevitable outcome of the victimisation of the rioters—the riot as revenge—he added: “Plus there’s an accumulated sense of grievance—the full extent of which I don’t pretend to know” (Australian Associated Press).

In addition to denying racism, Howard’s remarks cunningly tap into longstanding narratives that align Muslim and Arab youths with delinquency, gangs and criminality. Scott Poynting, who has written extensively on this issue, examines a variety of complex factors that led to the Cronulla riot, among them the ongoing perpetuation of exaggerations and myths about the behaviour of young Lebanese-Australians on Sydney’s beaches:

Folklore had circulated about how, for years, young “Aussie” women had been offended and insulted and made to feel unsafe on the beach by the young men of an essentially misogynistic and unAustralian culture. According to this story, the locals of Sutherland Shire . . . had for years been “putting up with” immigrant outsiders from the working-class western suburbs who, in addition to affronting “our women”, were exclusively responsible for littering the parks and beaches; uniquely involved in boisterousness and skylarking; played football on the sand; and dressed inappropriately for the beach by wearing too many clothes. (“What Caused” 87)

After a brief expression of shame following the riot, media and political attention shifted swiftly and disproportionately to the reprisal attacks, “return[ing] to the story of deviance and incivility of so-called ‘gangs’ of Lebanese or Muslim youths” (Poynting, “Scouring” 52). Given the ongoing demonisation of Arabs and Muslims in the Australian media and political discourse, this was hardly surprising. As Poynting explains, “[s]ince the mid- to late 1990s, the folk demon of the Middle Eastern/Muslim ‘other’ has been constructed, in societies like Australia, as backward, uncivilized, irrational, violent, criminally inclined, misogynistic and a terrorist threat—a whole litany of evil attributes” (“What Caused” 88–9). Indeed, the Arab, Middle Eastern or Muslim Other had emerged well before the riot as “the pre-eminent ‘folk devil’ of our time” (Poynting et al. 3), and recent global and national events—such as the terrorist attacks in New York and Bali, and the moral panic surrounding the “ethnic gang rapes” in Sydney in the early 2000s (Collins et al. 35–6; Dagistanli 181–2)—had only strengthened its construction.

It was this context in which politicians and police would produce “virtually even numbers of arrests, charges and prosecutions of revengers as of original perpetrators”, despite the massive disparity in the number of perpetrators involved in each event, and in which the media would soon dedicate “more air time and column inches to the revenge rioters and demands for their punishment, than to the original rioters” (Poynting, “‘Thugs’ and ‘grubs’” 167). Through the reframing of the Cronulla riot as a legitimate and proportionate response to the rioters’ preexisting grievances, the racial element of the riot is denied and, by extension, the reprisal attacks are able to be exploited as a surplus—that is, as yet another example of ongoing antisocial or criminal behaviour. As can be seen, the symmetrical “riot and revenge” narrative is a distortive one, and it also allows the boundaries of where the symmetry begins and ends to be shifted for various political ends. It is this precarious terrain that Forsythe’s film engages with.

Because the beach riot is relegated to the level of context, Down Under appears initially not to endorse the “riot and revenge” narrative outlined above. Forsythe constructs a symmetrical narrative around the events after the beach riot; in other words, he focuses on the second half of the paired sequence of events that has come to define how the Cronulla riot is understood. In many ways, it is a logical decision. Putting aside the financial and logistical difficulties in restaging a riot of this scale for a relatively low-budget film (under $3 million AUD), structuring a symmetrical narrative around the beach riot would be a tricky proposition given that most viewers would be well aware of how asymmetrical it actually was. Although the reprisal attacks were quickly used to deflect attention from the racial violence at Cronulla, the prevailing images of the events are from the initial media coverage of the beach riot, of lone men being surrounded and bashed by mobs of white men who targeted them for their ethnic appearance and literally nothing else (near-victims included two Bangladeshi students who narrowly escaped in their car as it was smashed, stomped on and pelted with bottles). Even the The Daily Telegraph, which had so often led the charge against the behaviour of Arab youths leading up to the riot, opened with the headline “Our Disgrace” on the morning after the riot, accompanied by a photograph of a group of men kicking and punching a defenceless man on the train (the man was Ali Hashimi, a Russian-born Afghan; the iconic photograph by Craig Greenhill, titled “Train Bashing”, would go on to win a Walkley Award and the 2006 News Awards Photograph of the Year).[4]

This was clearly not a traditional race riot in which the discontent of a minority group bubbled to the surface, but one in which a dominant group turned violently on minorities—and both the nation and the rest of the world recognised this immediately. As Gillian Cowlishaw describes it, the Cronulla riot is “distinctive in that it is not a subordinate group protesting . . . This is a segment of the dominant group protesting because it imagines itself as marginalised, as being progressively provoked, depowered and humiliated” (295). To make this distinction clear, historian Dirk Moses makes a convincing case that the violence in Cronulla can be defined as a pogrom, namely “violent attacks by majorities against minorities . . . [designed to] put the subordinate minority group in its place.” Viewed in isolation, the reality of the mob violence in Cronulla was so unambiguously brutal and one-sided, and so transparently driven by racism that any attempt to impose some sort of symmetry on it would be nothing short of a wilful act of denial. The Cronulla riot simply cannot sustain symmetry, because it was so plainly and visibly asymmetrical. No white rioter walked away that day as a bloodied victim.

On the other hand, structuring a symmetrical narrative around the period of the revenge attacks is a simpler proposition for a filmmaker because it was, and remains, a far less visible series of events. These attacks were more spontaneous and dispersed than the beach riot, occurring across a larger timeframe (two nights) and scattered across a wider area (several suburbs, including Cronulla but also Maroubra and Brighton-le-Sands). As horrific and arbitrary as the reprisal violence was, it occurred mainly out of sight of TV news cameras and under the cover of night. Because of the relative absence of images and the nature of the few images that did emerge (mostly, blurry CCTV footage), these events do not exist in the public consciousness with the same visual clarity as the beach riot. The opportunity for a filmmaker to conceive a fiction around this chaotic period of events is opened up greatly, for there is much less information by which most viewers would be able to corroborate their understanding of what occurred. While the “riot and revenge” narrative may not be reflected wholesale in the film’s structure (in that it is not split equally between the riot and the revenge attacks), Down Under provides a micro-view of the latter half of this narrative that nonetheless assumes its wider symmetry to be the true state of affairs. The very premise of the film, which consigns the riot to context and adapts the “revenge” events to accommodate a plot about two equally misguided groups whose flaws, aims and circumstances are afforded equivalence, takes for granted the “riot and revenge” narrative.

It is not my contention that Forsythe’s film sets out to disavow the racism underlying the Cronulla riot, as others have done. The filmmaker’s stated intention is the exact opposite—“The movie is about racism and how it basically stems from ignorance” (Maddox)—and the film does offer insight into racist attitudes and contemporary race relations in Australia. No doubt the film’s symmetry is designed in part to present both sides of the argument, and to explore issues of race without alienating either side (in interviews, Forsythe is much more partial in his critique of racism than the film is). By adopting this diplomatic approach, however, the film’s antiracist message flounders. At best, the issue of race is absorbed into the film’s structure and becomes heavily muted; at worst, it is offset by the structure and becomes neutralised. As happened in the popular discourse surrounding the Cronulla riot, the form of the discussion obfuscates the context. Precisely because of the careful balances it imposes, Down Under reinforces the distortive implications of the “riot and revenge” narrative, and inadvertently camouflages the racism and structural power imbalances that informed the Cronulla riot, and which continue in Australia to this day.

Figure 2: The theatrical poster. Down Under. Studio Canal, 2016.

A Balancing Act

The symmetries of Down Under begin outside of the film, via the film’s memorable marketing materials (designed by the creative agency The Monkeys). These extratextual elements warrant discussion because they are tightly integrated into the broader design of the film and were created with Forsythe’s close input; he describes working with the agency as one of the “creative highlights” of the production (Meikle). The simple and consistent designs all feature an orange-yellow gradient background—a hue that evokes the beach, sand and sun—upon which images of Anglo-Australian culture and Islamic culture are juxtaposed. In one example, an overhead shot of a blonde woman paddling on a surfboard on the left half of the image is paired with a similar shot of a Muslim man kneeling on an Islamic prayer rug, on the right. Other examples include the pairing of objects, for example, a bong and a hookah pipe, a thong and a sandal. In each instance a caption states, “AUSTRALIA V AUSTRALIA – NOBODY WINS”.[5]

The most prominent design features two characters staring wide-eyed towards the lens: a man in Ned Kelly’s helmet and body armour, and a woman wearing a niqab. The superficial visual symmetry (two characters who both have their faces covered and their eyes visible) is accentuated in the theatrical poster, a portrait variation of the same design which evokes a symmetry painting on a folded piece of paper. The woman is placed on the top half and Ned Kelly on the bottom half, upside down, with the title font dividing them; “Down” is written upright and “Under” is inverted. Conceptually, however, the symmetry is unbalanced. Ned Kelly is an individual, mythologised folk hero from the nineteenth century who was also a violent criminal (Davey and Seal 168), while the woman wearing the niqab represents many actual people living today and connotes violence only in the eyes of those who misunderstand the wearing of the niqab “as a practice synonymous with religious fundamentalism and, as such, one which fosters political extremism” (Zempi 1738). The niqab is taken out of its everyday context as an item of religious clothing and juxtaposed with Ned Kelly’s armour, which was designed to stop bullets. The significance of the woman wearing the niqab is thus shifted from the general (a figure that represents an articulation of Islam, and a type of person) to the specific (a character), while Ned Kelly’s individuality remains stable. The latter maintains his existing meaning and iconic status as an outlaw “fighter”—the poster would make little sense otherwise—while the visual symmetry and caption position the woman as an ideological “opponent” whose meaning in this context is derived from her opposition to him.[6]

The film itself establishes a series of juxtapositions in a similar fashion, most notably through the pairing of characters from both sides of the conflict—and this occurs on both the level of the group and the individual. Both groups are comprised of four young men and, while they do not look at all similar, each character has a counterpart in the opposite group whose traits and function are similar to his own. The two protagonists are reluctant participants: Hassim (Lincoln Younes) is an earnest student whose decision to join the group seems mainly to do with learning the fate of his younger brother, who has been missing since the day of the riot; the corresponding character is Shit Stick (Alexander England), a benign stoner and video-store clerk who is naively swept along by his racist peers. Both groups also feature volatile alpha-male characters—drug dealer Nick (Rahel Romahn) on one side, father-of-two Jason (Damon Herriman) on the other—who are self-appointed ringleaders and whose hatred for the other side is much greater than the others’. Equally, there is a paring of characters whose primary role is to provide comic relief: D-Mac (Fayssal Bazzi) is a goofy rap enthusiast who appears to be coming along for fun, while Ditch (Justin Rosniak) is a dedicated racist whose racism is made to seem innocuous by his simpleminded-ness. The latter spends most of the film with his head and face wrapped in bandages, under which is later revealed to be a new tattoo of Ned Kelly’s helmet: a uniform coat of black ink that covers his entire face, leaving only a slit for the eyes (“It looks like you’re wearing a fucking burqa”, Jason remarks, drawing a direct conceptual link between the film and its marketing materials). Finally, Ibrahim (Michael Denkha) and Evan (Christopher Bunton) are both relatives of the protagonists: the former is Hassim’s uncle and a devout Muslim, while the latter is Shit Stick’s younger cousin who has Down Syndrome. These two characters form a less obvious pairing than the others but they share a similar function as outsiders, both within their immediate groups and the broader society. It is possible that Ibrahim is not an Australian-born citizen like the others in his posse (Hassim mentions that he is “visiting”), and his poor English, failure to grasp social conventions and religious conservatism often put him at odds with his group. Meanwhile, Evan is infantilised by his peers because of his disability. Ditch explains to Graham (Marshall Napier), Shit Stick’s father, that Evan can’t join them because “he’s a ‘mong’”, while Doof (Christiaan Van Vuuren), another local ringleader, demands that Evan bash a “Leb” with a bat to prove himself capable before joining their expedition.[7]

Having established two sets of characters that mirror each other, the film depicts the parallel paths of both parties, structuring a narrative that stresses their shared qualities, flaws and aims. The narrative trajectories of the individual characters are also mirrored according to their pairing. Both protagonists are “recruited” in their respective workplaces (Shit Stick from the video store, Hassim from the kebab store) and end up committing violence despite their apparent pacifism. Hassim unleashes a severe beating upon a man who attacks Nick, and is front and centre at the final battle at the beach; Shit Stick holds his cool for longer, but fires his rifle at the opposing group in a blind rage after Evan is accidentally killed (it backfires and Shit Stick is wounded). At the end of the film, they are the last men standing. The alpha-male characters, Nick and Jason, are both emasculated at various points in the narrative. Nick falls into a confused silence when confronted by evidence of his own macho stupidity and, despite his regular sexist and homophobic remarks, it is suggested that he is gay (he responds violently to gay jokes directed at him, and tries to kiss Hassim after he saves him from a bashing). Jason becomes meek when in the company of more boisterous macho characters such as Doof and Graham, and is constantly bossed around by his heavily pregnant partner Stacey (Harriet Dyer). At one point, he leads a reckless charge against a kebab store under the pretext of committing revenge, but is actually heeding to Stacey’s demand that he brings home kebabs and a Turkish pizza for a late-night snack—a fact later revealed to Shit Stick, who forces him to admit that he is “pussy-whipped”. D-Mac and Ditch behave as annoying sidekicks to the alpha-male ringleaders throughout the film, and are eventually drawn to each other in the final battle, wrestling clumsily on the ground before being knocked out by others. Ibrahim remains unconscious for the entire fight, emphasising his inability to contribute or fit in, while the constant pressure to be accepted proves to be Evan’s downfall. After the kebab store robbery, he tries to manoeuvre the getaway car but succeeds only in stalling it, and when he later attempts to take the wheel during the beach battle (after being instructed by Shit Stick to sit out the fight), he accidentally reverses it off the cliff and to his death.

Forsythe goes to great lengths to imbue characters from both sides with a balancing set of prejudices. After Nick’s visit to Hassim’s house, during which he calls Ibrahim a “bearded fag”, he steps outside and sexually harasses two schoolgirls who pass by on the sidewalk (“You sluts want to suck me off?”). During a visit to Vic (David Field), a psychopathic and flamboyantly gay drug dealer who gifts the group a handgun, Ibrahim returns from the toilet to find the group conversing in the living room and notices a gay porno video playing behind them; he vomits onto the floor and throws a tantrum, prompting the entire group to be evicted. The final encounter between the opposing groups is precipitated by D-Mac’s homophobic taunts to Nick, who physically retaliates, causing their car to crash into Shit Stick’s. These characterisations evoke the racialised narratives of Arab and Muslim misogyny, delinquency and conservatism which were used as an immediate pretext for the Cronulla riot (and afterwards, as an explanation or justification for it). However, as if to offset these characterisations, the Anglo characters regularly hurl sexist and homophobic abuse also, to the extent that women and gays become the butt of most of the jokes in the film. When Ditch explains to Doof that he needs to rub moisturiser on his new tattoo, the latter mocks him with homophobic remarks. Jason verbally abuses an elderly woman in the video store who tells him to watch his language (“Why don’t you go suck a bag of dicks?”); jokes disparagingly about the promiscuity of Shit Stick’s ex-girlfriend; and, after a passionate diatribe about “wogs” disrespecting women, he answers a phone call from Stacey with, “What do you want, cunt?” Racist remarks by the Shire group are constant, but on the other side, Nick is also given an opportunity to display his casual racism. In a scene at the petrol station, he responds to the friendly interjection of the attendant behind the counter (who is of Pakistani descent) by telling him to “go eat a curry”.

Most of these insults register as didactic because their structural significance is transparent. With only a couple of exceptions, the insults have no consequence within the narrative and are presented as asides. They are uniformly jarring and excessive, and their effect is felt most obviously in relation to a corresponding insult—as part of a whole—rather than as individual insights into characters’ personalities, prejudices and motivations. For example, the abruptness and randomness of Jason’s insult towards the old woman recalls immediately Nick’s similarly worded insult directed at the schoolgirls a couple of scenes earlier. Likewise, Nick’s racial insult alludes to a previous scene in which Ditch taunts Shit Stick’s Indian co-worker (“What the fuck are you looking at, Curry Muncher?”) who is caught staring at his bandaged face. Nick’s words register less as a persuasive example of racism by one member of a minority group to another, and more obviously as the second half of a symmetrical pairing completed by the delivery of a similar racial insult in a similar setting. Despite these mirroring sets of prejudices, each group becomes defined by forms of prejudice that it pronounces more intensely and consistently than the other group; incidentally, these correspond to the forms of prejudice with which the representative groups were associated before and after the Cronulla riot. In other words, the Anglo-Australian rioters from the Shire are predominantly racist (but can be misogynistic and homophobic too), while the Lebanese-Australians are predominantly misogynists and homophobes (but can also be racist) and also turn out to be Muslims. The two groups settle into their pre-existing roles within the “riot and revenge” narrative: the Shire group are caricatured bigots whose racism and exaggerated sense of national pride are presented as exceptional rather than normal, while the film does little to dispel the unfounded notion that Lebanese-Australian youths are connected with delinquency and criminality.

It must be noted that there are several moments where Forsythe disrupts the racial binaries of the film, and presents race relations and racial categories as more dynamic and complex than the film’s structure might otherwise suggest. These are all centred around minor characters. For example, Evan is about to strike a passer-by with a baseball bat (at Doof’s urging) when the near-victim is revealed to be the Asian owner of the local newsagency; Jason appears to like the man and apologises after he is berated for referring to him as a “chink”. Later, when the same group attacks the kebab store, they are unsure whether the attendant is a “Leb” or a “wog”, and a panicked discussion ensues after they realise that a customer is still in the store and demand to know his ethnicity (he turns out to be a New Zealander). Meanwhile, in order to obtain a gun, the other group is happy to engage with Vic, a white gay male who surrounds himself with Thai servants. Ultimately, most of the recipients of racial abuse in the film are shop attendants, underlining the everyday interactions which both groups of characters must necessarily engage in as members of a multicultural society. However, in a similar vein to the symmetrical insults, these instances turn out to be momentary disruptions only; they have no impact on the course of the narrative and do not destabilise the film’s overall sense of symmetry.

Forsythe reinforces and expands upon the symmetries I have outlined above, through a variety of formal approaches. The most bombastic displays of film style in Down Under are two slow-motion sequences of each group of men doing burnouts in their cars, “looking both elated and aggressive, and at this glacial speed, somehow moronic as well” (Di Rosso). This first occurs when Nick screeches off down the street after convincing Hassim to join the group, then again after the Shire group meet up with Doof’s group and set off in two separate cars. A commercial pop song accompanies both sequences: Paula Cole’s “I Don’t Want to Wait”for the first and Kelis’s “Milkshake”for the second. In each instance the framing emphasises the pair of characters in the front and back seats, in separate shots; even the seating arrangements within the cars are mirrored, with Nick/Jason behind the wheel, D-Mac/Ditch in the passenger seats, and Ibrahim/Evan and Hassim/Shit Stick occupying the back seats. The second and lengthier slow-motion sequence begins with a bird’s-eye wide shot of one car leaving a series of circular tyre marks as it spins around, while the second car orbits around the first. The circular imagery recalls an earlier scene involving the opposite group, whereby the camera performs 360-degree pans in the middle of the car as the men inside argue. These accented examples of film style have a clear narrative and thematic function, emphasising the macho subcultures to which both groups of men belong, as well as providing an ironic commentary on these subcultures. Moreover, through their pairing they also reinforce a perpetual impression of symmetry that is felt as much as it is understood.

A similar effect is achieved by subtler means, through editing. Most of the film adheres to a conventional continuity-editing style within scenes, and alternates between self-contained sequences—focusing on one group and then the other—in a straightforward, linear fashion. In the early stages of the film, aerial shots of different parts of Sydney are used to punctuate the narrative as if they are chapter headings, announcing a shift from one sequence to the next and the location where the upcoming sequence will take place. However, as the film progresses these transitional markers disappear and the opposing sequences begin cutting directly to and from one another. Forsythe eventually connects sequences without making it immediately clear that a transition has occurred—a strategy that emphasises the closing of the gap between the groups, on both a narrative and formal level. For example, after speeding over a bump that causes the trunk to open and spill its contents onto the street, Jason talks to Stacey on the phone in the foreground while the others clean up the mess in the background. The next scene begins with shots of scenery filmed from inside a moving car, creating the impression that the Shire group have simply resumed their journey. However, a cut to the inside of the car reveals that the narrative has switched over to the opposite group. Similarly, after a later scene in which Shit Stick tucks Jason’s daughter into bed on his way out of Stacey’s house (where Jason has dropped off the kebabs for her), Forsythe cuts to shots of passing scenery from inside a car. Again, it is not until there is a cut to the inside of the car that it becomes apparent that the narrative has shifted back to the other group.

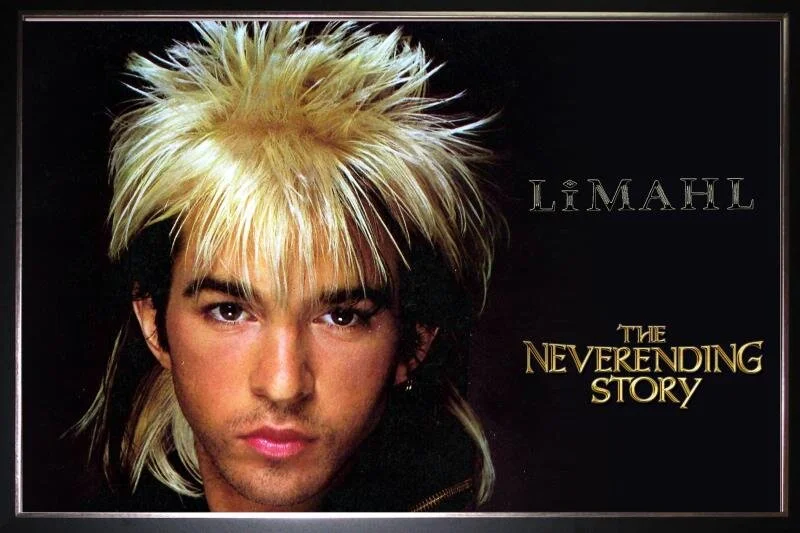

After the second slow-motion burnout sequence, the action moves to scenes of police roadblocks as young Middle Eastern men are searched for weapons and arrested. Despite the geographical shift—perhaps more obvious to viewers aware of the layout of the city and where the actual events unfolded—the escalating narrative (underscored by frequent cutting and handheld camerawork) and the continuing pop song on the soundtrack maintain the impression that the narrative is still following the Shire group. Then Ibrahim drives past, with his three companions ducking down and hiding, and the scene shifts to inside their car. The camera settles on a medium close-up of Hassim as he sits up in the backseat, positioned in the right half of frame, and a new song takes over on the soundtrack (Limahl’s theme song from The NeverEnding Story). The song continues over the next shot, which is a reverse framing of petrol containers in the opposite back corner of Shit Stick’s wagon. Despite the different content of the shot, the consistent soundtrack and visual elements (mirrored compositions, comparable lighting and depth of field, and similar scenery passing by at a similar pace outside the car) create the immediate impression that the narrative is still following the same group in the same car. In this instance, Forsythe applies the shot/reverse-shot editing pattern—a conventional method of scene coverage and a symmetrical formal system in itself, in that it connects two mirrored compositions to construct a cohesive, spatiotemporal whole—across scenes to create a direct visual match between the groups. While early scenes in Down Under alternate transparently between the two opposing groups in sequence, the later scenes shift gradually towards a parallel editing pattern, creating the illusion of both simultaneity and shared space—that is, a shift from a structural symmetry to an impression of spatiotemporal symmetry.

Figure 5: One of the film’s slow-motion burnout sequences. Down Under. Studio Canal, 2016.

These mirroring narrative and formal strategies reach a crescendo during the final climactic sequences. The Shire group have just left Stacey’s house, the western suburbs group have left a violent encounter with Doof’s crew, and both resume their journeys by car. Forsythe begins cutting back and forth between them as they drive through the night streets. Again, the compositions are mirrored (a wide shot from the bonnet, looking back inside the car) as are the actions of the characters: Jason sits in annoyed silence as Shit Stick and then the others sing along to Natalie Imbruglia’s “Torn”, while in the other car D-Mac teases Ibrahim and Nick through freestyle rap. When D-Mac strikes a nerve by rhyming “our friend Nick, he loves sucking dick”, Nick lunges at him, causing Ibrahim to collide into Shit Stick’s car approaching from the opposite direction. The accident forces the first physical meeting between the groups and leads to an overtly symmetrical composition that contains them within the same shot, for the first and last time. The cars face each other in a wide shot and meet in the centre of frame as smoke bellows out between them; the men emerge from the cars on both sides of the image as they come to their senses. Upon realising that the opposite group are “wogs”, Jason begins bashing Hassim with the baseball bat, but is interrupted by Nick who fires a warning shot into the air. The Shire group scramble back into the car and attempt to flee, and duck for cover as Nick fires sporadic shots at them. An absurdly slow car chase ensues as Nick, who is now behind the wheel, pursues the other (equally damaged) car.

They arrive at a rocky beach where the balancing equivalences seen throughout the film are accelerated in a flurry of violence. A symmetrical standoff is staged after the Shire group realise they have reached a cliff and perform a U-turn, leaving them facing the other car which, like theirs, has only one working headlight. The three members of each group stand facing each other from a distance as Forsythe cuts between them in a series of mirroring reverse-shots. Ibrahim’s absence (he lies in the car unconscious from the crash) is quickly offset by Evan’s abrupt death. Both groups have one bullet remaining at the start of the fight; Evan’s death prompts Shit Stick to be the first to fire his rifle, and the violence comes to a halt when Nick shoots Jason with his last bullet. In between these two bookending gunshots, the characters attack each other one by one, the symmetry of the fight broken and then resumed as one character takes down another and is then taken down himself. Eventually, nobody is left standing. The final two shots of the film are of each protagonist lying wounded and demoralised on the beach as the sun rises. Shit Stick is framed in medium shot, holding his bloodied face and looking into the distance. Then the symmetry dissipates momentarily as Hassim is framed in wide shot waking up to the beeping of his phone; as he listens to a voicemail message left by his brother, who is safe and sound, the camera tracks in slowly and settles on a reverse angle of the previous shot. The symmetry is restored, and the film ends.

Conclusion

In the Four Corners “Riot and Revenge” report, Eiad Diyab, a young Lebanese-Australian law student who had been swimming at Cronulla Beach all his life, describes how “everyone was shattered” and “almost in tears” upon watching images of the riot on the news. He then explains the pain of being told that he does not belong, in a place he has long called home:

I mean, all your life you’ve been—you’ve been raised to be Australian. I mean, you carry the Australian flag. When you go to sports events and all that, you’re happy to be Australian and all that. And all of a sudden, people reject you. “Go home!” They shout your names. Like, “Go home, you Middle Eastern Lebs”, or whatever. “Go home.” I mean, that’s a shock to us. “Go home.” I mean, like, you get cut inside your heart, you know. Like you feel like you’re not part of society no more.

Diyab made the choice not to seek revenge but understands why others did. “I’m not saying it’s correct, what they did”, he says, “but you can’t just sit there and just take it. I mean, you’ve gotta respond to that situation and protect yourself.”

As Amanda Wise writes in relation to the responses of young Arab men after the Cronulla riot, “the deep wounding of racism can create a disposition of violent and group-oriented defensiveness among alienated young men and produces a sense of protest masculinity in response to that racism” (138). Down Under depicts very clearly the behaviours that Wise describes; what is missing from the film are signs of the “deep wounding of racism” that provides the crucial context for these behaviours. The constant mirroring of masculine-aggressive behaviour on both sides of the conflict further obscures the racial context and the fact that one is a group of “alienated young men”, while the other is not. Also absent from the film’s focus are the political and societal issues underlying the riot; for example, the well-documented role of the media in exacerbating racial tensions, and the damaging political discourse surrounding race, immigration and multiculturalism. As Jason Di Rosso observes, the almost complete lack of a broader context for the riot “means the film presents its story of two very different groups of young men—one Arab, the other Anglo—as almost interchangeable.”

Although it is still possible to feel and identify the film’s antiracist sentiments, Down Under is in the end a pointed study of masculine aggression and only a superficial examination of race and racism. As the first narrative feature film to be based on the Cronulla riot, it offers a new medium through which to explore its ramifications. However, the film’s contribution to the discourse surrounding the riot is a retreading of familiar territory, presented in a new form: a cinematic rendering of the “riot and revenge” narrative. The problematic nature of Forsythe’s film has little to do with the fact that it is a comedy, but with its process of “levelling out”; its shifting of the context away from race and in its distributing blame and responsibility equally among the racial divide so that it appeases everyone and confronts no one. Its rigorous use of symmetry as a narrative, thematic, structural and formal device presents as equal the experiences of two groups in Australian society when in fact they were, and remain, anything but equal.

Notes

[2] In addition to reading out the inciteful text message, Jones referred to those who assaulted the lifesavers as “Middle Eastern grubs”, suggested that biker gangs be present at Cronulla railway station to confront “Lebanese thugs”, responded to a caller who protested about the on-air racism by telling her that “[w]e don’t have Anglo-Saxon kids out there raping women in western Sydney”, and gave airtime to callers who proposed vigilante action (Marr 61–3). In April 2007, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) released a report which found that Jones and 2GB had breached the radio code of practice on three separate occasions leading up to the riot, broadcasting material likely to “encourage violence or brutality” and to “vilify people of Lebanese background and people of Middle-Eastern background on the basis of ethnicity.”

[3] Although it is the first narrative feature film to be based on the Cronulla riot, Down Under follows a long line of responses by Australian artists and academics—for example, Anne Zahalka’s photographic series Scenes from the Shire (2007), Vernon Ah Kee’s installation cant chant (2007–2009), Jaya Balendra’s interactive documentary Cronulla Riots: The Day that Shocked the Nation (2013), and numerous academic studies such as Greg Noble’s edited collection Lines in the Sand (2009) and Amelia Johns’s book Battle for the Flag (2015). Down Under is also not the first screen comedy to tackle the riot. In 2007, Paul Fenech’s TV series Pizza released a two-part episode titled “The Beach”, in which a Lebanese-Australian pizza driver and his friend accidentally trigger a riot at Cronulla Beach. In the same year, Jayce White’s short comedy Between the Flags, about two young rioters from opposing sides who form a friendship after arriving at the wrong beach, was a finalist in the Tropfest short film competition.

[4] For this photograph and Greenhill’s account of the riot, see Greenhill (“If I Wasn’t on That Train”).

[5] See Shannon for examples of these marketing materials.

[6] Incidentally, Forsythe’s first feature film Ned (2003) was a comedy about Ned Kelly.

[7] Both groups of characters can also be aligned to longstanding traditions in Australian screen comedy. The Shire characters can be seen as variants of those found in the “ocker” films of the 1970s—such as Tim Burstall’s Stork (1971) and Petersen (1974), and Bruce Beresford’s The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972) and Don’s Party (1976)—which were characterised by their “unabashed celebration of the ‘Australian’, particularly the vernacular, whether in speech, content, or action” (O’Regan 76). Meanwhile, the Lebanese-Australian characters evoke “the vulgar assertion of recent immigrant identities as performative variations on brash Australian masculinity” (Speed 161) in more recent works such as Aleksi Vellis’s The Wog Boy (2000) and the aforementioned Pizza TV series.

References

1. Ah Kee, Vernon. cant chant, multimedia installation. 2007–2009, Corrigan Collection.

2. Arnheim, Rudolf. “Symmetry and Organization of Form: A Review Article.” Leonardo, vol. 21, no. 3, 1988, pp. 273–6.

3. Australian Associated Press (AAP). “PM Refuses to Use Racist Tag.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 Dec. 2005, www.smh.com.au/news/national/pm-refuses-to-use-racist-tag/2005/12/12/1134235985480.html. Accessed 1 Nov. 2016.

4. Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA). “Investigation Report No.1485.” ACMA, 2007, www.acma.gov.au/~/media/Broadcasting%20Investigations/Investigation%20reports/Radio%20investigations/pdf%20pre%202013/2gb_report1485%20pdf. Accessed 1 Apr. 2017.

5. Awad, Amal. “Down Under review: Cronulla Riot Racism Comedy Swings, Misses.” SBS, 7 Aug. 2016, www.sbs.com.au/movies/review/down-under-review-cronulla-riot-racism-comedy-swings-misses. Accessed 15 Oct. 2016.

6. Balendra, Jaya, director. Cronulla Riots: The Day that Shocked the Nation. SBS, 2013, www.sbs.com.au/cronullariots/. Accessed 1 Oct. 2016.

7. “The Beach.”Pizza, created by Paul Fenech, season 5, episodes 4–5, SBS, 2007.

8. Beresford, Bruce, director. The Adventures of Barry McKenzie. Umbrella Entertainment, 1972.

9. ---. Don’s Party. 20th Century Fox Australia, 1976.

10. Burchell, David. “Both Sides of Political Divide Stoop to Playing the Race Card.” The Australian, 27 Jan. 2016, p. 12.

11. Burstall, Tim, director. Petersen. Roadshow Film Distributors, 1974.

12. ---. Stork. Roadshow Film Distributors, 1971.

13. Cole, Paula. “I Don’t Want to Wait.” This Fire, Imago/Warner Bros., 1996.

14. Collins, Jock, et al. Kebabs, Kids, Cops and Crime: Youth, Ethnicity and Crime. Pluto Press, 2000.

15. Cowlishaw, Gillian. “Introduction: Ethnography and the Interpretation of ‘Cronulla’.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology, vol. 18, no. 3, 2007, pp. 295–9.

16. Dagistanli, Selda. “‘Like a Pack of Wild Animals’: Moral Panics Around ‘Ethnic’ Gang Rape in Sydney.” Outrageous! Moral Panics in Australia, edited by Scott Poynting and George Morgan, ACYS Publishing, 2007, pp. 181–96.

17. Davey, Gwenda Beed, and Seal, Graham. A Guide to Australian Folklore: From Ned Kelly to Aeroplane Jelly. Kangaroo Press, 2003.

18. Devine, Miranda. “Gangsters’ Hold on Sydney is Safe.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 22 Dec. 2005, www.smh.com.au/news/opinion/gangsters-hold-on-sydney-is-safe/2005/12/21/1135032077070.html. Accessed 1 Oct. 2016.

19. Di Rosso, Jason. “Cronulla Riots Film ‘Down Under’ Pulls Punches.” ABC RN, 17 Jun. 2016, www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/finalcut/cronulla-riots-black-comedy-down-under-ruffles-few-feathers/7517244. Accessed 15 Oct. 2016.

20. Forsythe, Abe, director. Down Under. Studio Canal, 2016.

21. ---. Ned. Becker Entertainment, 2003.

22. Greenhill, Craig. “‘If I Wasn’t on That Train We Wouldn’t Have Proof of Australia’s Shameful Violence’.” The Daily Telegraph, 10 Dec. 2015, www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/if-i-wasnt-on-that-train-we-wouldnt-have-proof-of-australias-shameful-violence/news-story/43500de94f4f49ed72856ceaf74c8b31. Accessed 4 Sep. 2016.

23. ---. “Train Bashing.” The Daily Telegraph, 6 Dec. 2005.

24. Strike Force Neil. “Cronulla Riots: Review of the Police Response, Report and Recommendations, Vol. 1.” New South Wales Police, 2006.

25. Imbruglia, Natalie. “Torn.” Left of the Middle, RCA, 1997.

26. Johns, Amelia. Battle for the Flag. MUP Academic, 2015.

27. Kelis. “Milkshake.” Tasty, Arista/Star Trak, 2003.

28. Kelly, Paul. “Howard and His Haters Miss Real Migration Story.” The Australian, 21 Dec. 2005, p. 12.

29. Kolker, Robert. “Rage for Order: Kubrick’s Fearful Symmetry.” Raritan: A Quarterly Review, vol. 30, no. 1, 2010, pp. 50–67.

30. Limahl. “The NeverEnding Story.” The NeverEnding Story, EMI, 1984.

31. Maddox, Garry. “Cronulla Riots Film Director Abe Forsythe Says Australia Is More Racist Now.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 Jul. 2016, www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/cronulla-riots-film-director-abe-forsythe-says-australia-is-more-racist-now-20160719-gq8wbw.html. Accessed 8 Mar. 2017.

32. Marr, David. Panic. Black Inc., 2011.

33. McManus, I.C. “Symmetry and Asymmetry in Aesthetics and the Arts.” European Review, vol. 13, no. 2, 2005, pp. 157–80.

34. Meikle, Larissa. “The Monkeys Launches Provocative Campaign to Promote Abe Forsythe’s New Film Down Under.” B&T, 2 Aug. 2016, www.bandt.com.au/marketing/down-under-the-monkeys. Accessed 1 Dec. 2016.

35. Moore, Bruce. “Wog.” Ozwords, vol. 19, no. 1, 2010, pp. 1–3, andc.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/OZWords%20April%202010.pdf. Accessed 15 Apr. 2017.

36. Moses, Dirk. “Pogrom Talk.” On Line Opinion, 11 Jan. 2006, www.onlineopinion.com.au/view.asp?article=4038. Accessed 4 Nov. 2016.

37. Noble, Greg, editor. Lines in the Sand: The Cronulla Riots, Multiculturalism and National Belonging. Institute of Criminology Press, 2009.

38. O’Regan, Tom. “Cinema Oz: The Ocker Films.” The Australian Screen, edited by Albert Moran and Tom O’Regan, pp. 75–98.

39. Perera, Suvendrini. “Race, Terror, Sydney, December 2005.” Borderlands, vol. 5, no. 1, 2006, www.borderlands.net.au/vol5no1_2006/perera_raceterror.htm. Accessed 19 Jul. 2016.

40. Poynting, Scott. “Scouring the Shire.” Lines in the Sand: The Cronulla Riots, Multiculturalism and National Belonging, edited by Greg Noble, Institute of Criminology Press, 2009, pp. 44–57.

41. ---. “‘Thugs’ and ‘Grubs’ at Cronulla: From Media Beat-ups to Beating Up Migrants.” Outrageous! Moral Panics in Australia, edited by Scott Poynting and George Morgan, ACYS Publishing, 2007, pp. 158–70.

42. ---. “What Caused the Cronulla Riot?” Race & Class, vol. 48, no. 1, 2006, pp. 85–92.

43. Poynting, Scott, et al. Bin Laden in the Suburbs: Criminalising the Arab Other. The Sydney Institute of Criminology, 2004.

44. “Riot and Revenge.” Four Corners, Australian Broadcast Corporation, 13 Mar. 2006.

45. Shannon, Jackie. “Down Under Throws Down the Gauntlet.” FilmInk, 2 Aug. 2016, filmink.com.au/2016/down-under-throws-down-the-gauntlet/. Accessed 1 Apr. 2017.

46. Speed, Lesley. “Comedy.” Directory of World Cinema: Australia & New Zealand, edited by Ben Goldsmith and Geoff Lealand. Intellect Books, 2010, pp. 158–62.

47. Vellis, Aleksi, director. The Wog Boy. 20th Century Fox Australia, 2000.

48. Weyl, Hermann. Symmetry. Princeton UP, 1952.

49. White, Jayce, director. Between the Flags. Hyperdriven Media Services, 2007.

50. Wise, Amanda. “‘It’s Just an Attitude That You Feel’: Inter-Ethnic Habitus before the Cronulla Riots.” Lines in the Sand: The Cronulla Riots, Multiculturalism and National Belonging, edited by Greg Noble, Institute of Criminology Press, 2009, pp. 127–45.

51. Zahalka, Anne. Scenes from the Shire, photographic series. 2007, Art Gallery of New South Wales.

52. Zempi, Irene. “‘It’s a Part of Me, I Feel Naked without It’: Choice, Agency and Identity for Muslim Women Who Wear the Niqab.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 39, no. 10, 2016, pp. 1738–54.

Suggested Citation

McGrath, Kenta. “Riot and Revenge: Symmetry and the Cronulla Riot in Abe Forsythe’s Down Under.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media 13 (Summer 2017): 13–32. www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue13/HTML/ArticleMcGrath.html. ISSN: 2009-4078.