Solar Breath

Commissioned for The world is all cut-outs then exhibition at Goolugatup Heathcote (27 July – 7 September 2025), curated by Paul Boye. Featuring works by Marcus Camphoo, Clara Joyce, Michael Snow, Jimi DePriest and Nate Wood.

According to Michael Snow, Solar Breath (2002) is a film in which ‘[c]hance and choice coexist.’[1] The claim seems to border on the obvious: the same could be said of countless other films, including much of Snow’s own body of work. In fact, one could reasonably argue that chance and choice coexist in virtually any artwork, regardless of the degree of control the artist claims to have exercised or relinquished. Yet in the case of Solar Breath, Snow’s statement couldn’t be more apt. Here, chance and choice aren’t just present – they depend on each other, shaping one another in fragile equilibrium.

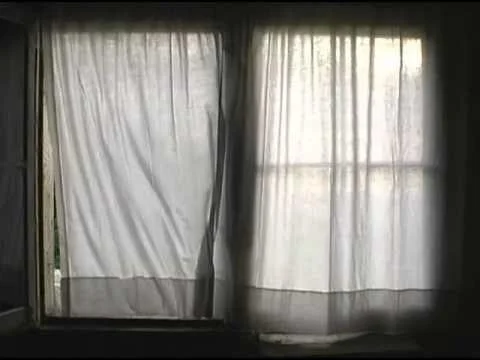

The film’s subject is an unusual phenomenon Snow observed inside his remote coastal cabin, where he and his wife, Peggy Gale, spent part of their summers. It unfolds in a static shot framing two adjoining windows – one open, the other closed – before which hangs a white cotton curtain. For the most part, the curtain behaves as expected: it filters sunlight, sways in the breeze and at times flaps high enough to reveal glimpses of the yard beyond (where some evergreens, stacks of firewood and a solar panel come into view). But every so often, it gets pulled back with surprising force, slapped against a near-invisible flyscreen and held there – each time forming a unique pattern of creases and folds – until the wind lets go. This cycle repeats uninterrupted, without cuts, for the film’s 62-minute duration.

Solar Breath was made possible by the extended recording capacity of video – a medium Snow embraced, though not typically for this kind of candid observation. Granted, there are precedents in his career: Dripping Water (1969), a 16mm collaboration with Joyce Wieland comprising a 10-minute shot of its namesake, or Sheeploop (2000), a video installation whose title likewise describes its content and structure. But rarely was Snow’s approach as restrained as simply framing a shot and leaving the rest to chance. By and large, his filmed work was marked by a conscious effort to disrupt time, fracture space and foreground its own construction. No such intervention occurs in Solar Breath.

Though designed for the gallery (projected at 79 inches wide, matching the dimensions of the actual window), Solar Breath is also notable within Snow’s oeuvre for the extent to which it intersects with broader cinematic lineages. Its affinity with the avant-garde’s durational experiments is readily apparent, while its openness to chance reflects the ideals of documentary’s observational tradition. Moreover, the emphasis on quietude, atmosphere and the everyday resonates with the so-called ‘slow cinema’ – a contemplative strand of art film that rose to prominence at the turn of the century. (In a parallel universe, Solar Breath could slot seamlessly into a film by the likes of Lisandro Alonso, Abbas Kiarostami or Apichatpong Weerasethakul.)

Windows, as it happens, are also among the most enduring and versatile metaphors in cinema. They often evoke the act of watching and being watched; serve as thresholds into other worlds (social, historical, psychological); and are frequently likened to the materials and mechanisms of the medium itself (filmstrips, projector screens, the cinematic frame). Solar Breath flirts with many of these associations but distinguishes itself in one crucial respect: its window isn’t meant to be looked through so much as it is to be looked at. Tellingly, the film’s rich array of oppositions – stillness/movement, flatness/depth, transparency/opacity, symmetry/asymmetry, to name just a few – all derive from a window whose view is ‘compromised’ from beginning to end.

As per Snow’s statement, the film’s central tension lies between what the artist could and couldn’t control. This is exemplified, among other things, by the brief but suggestive glimpses of the solar panel, whose presence contrasts with the otherwise rustic scenery. Constructed of metal, silicon and glass, this device requires careful positioning by human hands to function – yet its usefulness ultimately depends on the weather, something entirely beyond human control. In this instance, the panel also powered the camera’s battery via a cable threaded through the window. In more ways than one, Solar Breath wouldn’t have existed had the sun and sky not cooperated.

That said, Snow isn’t simply equating chance with nature and choice with everything else. The phenomenon captured in the film might be an accident of nature, but it relies on the alignment of other, non-natural elements – a cabin, a window and a curtain, for starters, all built or designed by Snow or Gale – for it to occur in the first place. Only then does artistic choice come into play: by waiting, watching, listening, framing and recording, the event can be preserved as image and sound, rendered usable for art (or whatever else). And even then, a mere mortal like Snow could never predict when or how the wind would blow, much less what it might do to a curtain. Given the rarity of the event – it was seen only once or twice each summer, and sometimes not at all – the fact that it was captured was, in itself, a stroke of luck.[2]

Chance governs choice at every stage, and yet only choice can make that chance visible and audible for others to contemplate, marvel at or be bored by. It really is, as Snow says, a coexistence – in the truest, loveliest sense of the word.

Notes

[1] Snow, Michael. 2005. “Life and Art: About Solar Breath (Northern Caryatids)”. In Michael Snow: Souffle Solaire/Solar Breath, 11. Montreal: Galerie de l’UQAM.

[2] Solar Breath, incidentally, followed several aborted attempts over the years, when the light wasn’t right or the wind failed to produce the desired effects.