Three Baddish Men: The Hidden Fortress

An essay commissioned for The Hidden Fortress UHD/Blu-ray, released by BFI in August 2025.

Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress (1958) is a rollicking, comedic adventure set during a turbulent era in Japan’s history – namely, the Sengoku (‘warring states’) period of the 15th and 16th centuries, when feuding warlords waged war after bloody war in their struggle for supremacy. Of the five films Kurosawa set against this backdrop – Seven Samurai (1950), Throne of Blood (1957), Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985) being the others – The Hidden Fortress is by far the most light-hearted. This is largely because its guide through the chaos isn’t a power-drunk lord, a vengeful princess or a band of noble warriors, but a pair of buffoons plucked from the lowest rungs of society.

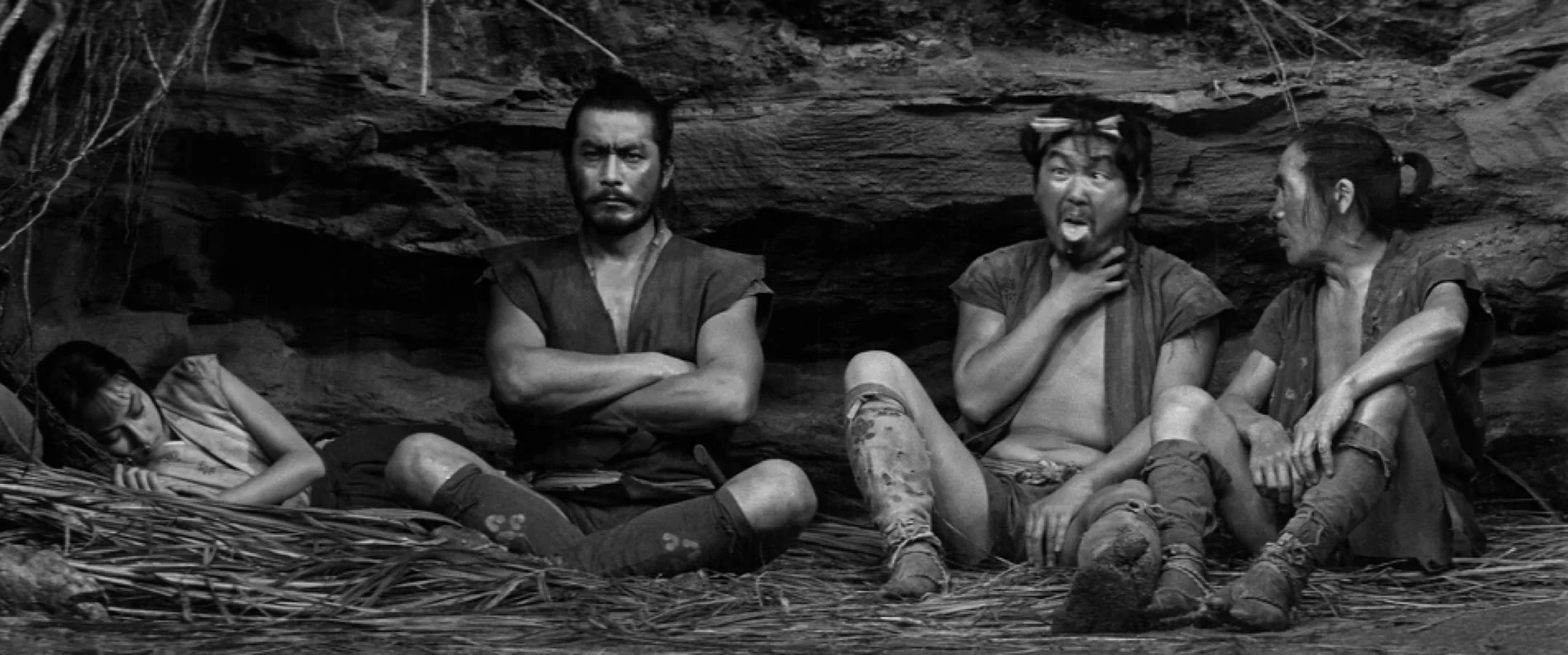

Then again, ‘guide’ might not be quite the right word. Tahei and Matashichi (played by Kurosawa regulars Minoru Chiaki and Kamatari Fujiwara, respectively) are peasants – little more than human ants, clinging on as they’re swept along by the forces of history. This much is clear from the opening scene, where we find the pair – one short and skinny, the other tall and plumpish, both equally dishevelled – shuffling across a barren plain. Their incessant bickering fills in the backstory: hoping for a share of the spoils in a war waged by the Yamana clan against its rivals, the Akizuki, the men had sold off their homes to get in on the action. But the plan went to shit before they ever saw battle. Having left it too late to enlist, they were mistaken for defeated Akizuki soldiers, imprisoned and enslaved, and eventually escaped without a penny or scrap of food to their name.

After a further string of mishaps, the pair strike it lucky when they stumble upon literal gold: a piece of Akizuki treasure hidden inside a branch of firewood. The catch is that it also marks the arrival of Rokurota Makabe (Toshiro Mifune) – a gruff, quietly intimidating figure, initially mistaken for a bandit. In fact, he’s a famed Akizuki general who has fled into the mountains (and to the titular hidden fortress) with a small band of survivors. Chief among them is Princess Yuki (Misa Uehara), an iron-willed royal of just sixteen, whose head is the last obstacle standing in the way of total Yamana victory.

For Rokurota, the useless peasants prove more than useful. Latching onto their plan to cross enemy lines into friendly territory, he decides to smuggle the Princess – and a considerable cache of gold – to safety, using the men as camouflage and tricking them into lugging a treasure they’ll never see a fair share of. He and the Princess will keep their identities secret, and to complete the ruse, she’ll pretend to be mute (she’s a royal, after all, and a particularly outspoken one at that). Tahei and Matashichi are vaguely aware they’re being played, but they don’t really care – since they, too, think they’re playing the others. And so begins a swashbuckling journey through war-torn lands, predicated on mutual deceit.

Although The Hidden Fortress is one of Kurosawa’s best-known and most popular films, its critical reputation over the years has, on balance, been rather tepid. Among scholars, the film is often glossed over as an entertaining and proficient, yet ultimately minor, work. More contentious is the widespread assumption, echoed repeatedly by critics, that the film represents a compromise: a piece of frivolous entertainment Kurosawa made primarily to advance his own career (which, to be fair, it very much did). Such a claim belies the fact that Kurosawa was the mainstream filmmaker par excellence, albeit one who fluctuated between reliable popular genres and riskier narrative fare throughout most of his career.

Granted, critics have always struggled to keep pace with the quantity and diversity of his cinematic output – especially during the early years following his belated discovery in the West with Rashomon (1950), his eleventh feature. When The Hidden Fortress landed on international shores – trimmed by 13 minutes from its original 139-minute running time, then later truncated to just 90 – most critics drew a direct line from Rashomon to The Hidden Fortress via Seven Samurai, seemingly uninterested in the remarkable films Kurosawa made in between, let alone earlier works like The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail (1945), with which it shares many similarities. Meanwhile, others appraised the film almost exclusively through its perceived Western influences, with the likes of John Ford, David Lean, Sergei Eisenstein and William Shakespeare serving as regular reference points. Among indifferent and receptive reviews alike, it became routine to describe The Hidden Fortress as ‘a Japanese Western’ – a label that, while not entirely inaccurate, rings hollow given it was also applied ad nauseum to Seven Samurai and later extended to Yojimbo, two films against which it would be unfavourably compared for decades to come.

While The Hidden Fortress often had to contend with the lofty benchmarks Kurosawa himself had set, the gulf between its critical and popular receptions may also stem from its position within his filmography. Not only does the film diverge from most of the director’s work in its lightness of tone, it’s also conspicuously wedged among some of his bleakest: arriving shortly after I Live in Fear (1955) and Throne of Blood – both of which chart their protagonists’ descent into madness with tragic grandeur – and sandwiched between The Lower Depths (1957), a grimy adaptation of Max Gorky’s play, and The Bad Sleep Well (1960), a revenge drama widely regarded as Kurosawa’s most pessimistic film. Next to these weighty themes and despairing narratives, The Hidden Fortress feels infinitely cleaner, lighter, safer. It’s no coincidence that its mixed reception resembles that of Sanjuro (1962), another period comedy beloved by audiences but often regarded by critics as insubstantial.

There’s still plenty of catching up to do, but the film’s reputation did gradually improve over the years – helped significantly by the re-release of the original cut some four decades after its debut, not to mention George Lucas crediting it as an inspiration for Star Wars (1977) in the interim. One aspect critics rarely failed to praise, however, is Kurosawa’s brilliant command of TohoScope (the Japanese equivalent of CinemaScope), an anamorphic widescreen format he adopted for the first time in The Hidden Fortress and continued to employ in all his remaining black-and-white productions through to Red Beard (1965). The formal possibilities opened up by this format were many, yet it led not to an overhaul but rather a refinement of Kurosawa’s style, deepening the range of his already diverse toolkit. The elongated frame of The Hidden Fortress houses sweeping visual compositions and intricate long takes, with the latter reaching heights of complexity previously unseen in his work; it also accommodates the bold close-ups, dynamic camera movements and rapid montage sequences that were already part of his bread and butter. Ever the versatile director, Kurosawa continued to embrace a broad array of cinematic modes and traditions that had long defined his practice.

Moreover, the expansive frame doesn’t necessarily correspond to a sustained increase in the viewer’s field of vision – or in the characters’ awareness of their surroundings. In fact, the opposite is often true. At the start of the film, for instance, the peasants traverse a wasteland that stretches as far as the eye can see, yet they still manage to get caught off guard: first by a bloodied samurai stumbling into the shot, scaring the bejesus out of them, then by a half-dozen Yamana soldiers who storm in on horseback, spear the man to death and then vanish offscreen as quickly as they appeared (it takes only a glance to dismiss the peasants as too insignificant to kill). Later, the same two men are again caught unawares while rummaging for gold in a clearing; elsewhere, entire armies seem to materialise out of the blue the moment one turns a corner or peers over a hill. In this manner, the widescreen image often becomes, in and of itself, something like a metaphor for short-sightedness – emphasising the characters’ inability to see what lies just ahead, despite the apparent vastness of their surroundings. Kurosawa thus draws upon a fundamental paradox inherent in the act of framing any image, regardless of its size or width: to show something is always, necessarily, to conceal something else.

It might be surprising to learn that the original Japanese title of the film (Kakushi toride no san akunin) translates to Three Bad Men in a Hidden Fortress, presumably referring to the trio of principal male characters. At first glance, it doesn’t quite fit. If the ample screen time devoted to Tahei and Matashichi scrambling up – then slipping down, then scrambling back up – various hillsides is anything to go by, these two seem far too clownish, too harmless, to warrant such a label. But to reduce them to mere fools would be to let them off the hook. It’s suggested more than once that they’d try to rape (or at least molest) the Princess if given half a chance, and their voracious greed would be considered grotesque in any other context. It’s true that these men are mostly innocuous, funny, and at times even lovable (indeed, they served as the blueprints for Star Wars’ C-3PO and R2-D2). But it’s also true that they’re degenerate scumbags.

Rokurota, by contrast, is a stoic, chivalrous warrior, defined by his unwavering loyalty to the Princess. These are hardly negative traits – until it’s revealed that his loyalty extends to sacrificing his own sister, whom he has sent into enemy hands as a decoy. His actions can be seen as a reflection of both the era and his particular ilk, but this piece of exposition nevertheless places him among a roster of Kurosawa protagonists – Murakami from Stray Dog, Nakaji from I Live in Fear and Nishi from The Bad Sleep Well among them – who cling to their moral convictions to the point of absurdity. The Princess, for her part, is plainly disgusted by his behaviour.

Ironic as it may be, the original title is one of several clues to darker undercurrents beneath the film’s comic veneer. An early set piece involving hundreds of half-naked men, herded like cattle into slave labour, is a disturbing sight softened only by the presence of Tahei and Matashichi among the crowd. Similarly, the gnarled forests and fog-covered landscapes could have been lifted out of Throne of Blood were it not the peasants who had to negotiate them. The violence isn’t exactly made palatable either, much of it prefiguring the bloodletting in Kurosawa’s later jidai-geki films (such as Yojimbo and Sanjuro, in terms of its visceral impact, or Kagemusha and Ran, in terms of its pointlessness).

In truth, Kurosawa’s cinema has always been marked by such contrasts. From the striking use of musical counterpoint in Drunken Angel (1948) and the comical intrusions of Stray Dog to the duel that brings Sanjuro to a sobering close, his films frequently bring together seemingly incongruous, and sometimes outright clashing, tonal elements. The contrasts in The Hidden Fortress are much more sustained, embedded as they are in some of its main characters rather than confined to certain shots or sequences. But here, as elsewhere, Kurosawa defines the parameters of his fiction with such conviction that its ingredients always remain acceptable, and believable – however incongruous, improbable or crowbarred-in they may seem otherwise.

The same can be said even for relatively minor narrative details. Take, for example, the treasure concealed in firewood: it’s a fun and clever conceit, but one that might risk outstaying its welcome from time to time, since burdening the characters with such a cumbersome load throughout would entail an unsustainably slow pace of travel (and therefore narrative progression) for a film of this sort. Accordingly, the group’s journey is punctuated by detours, downtimes and characters temporarily splitting up. And just as with the hidden fortress itself – more of an oasis, really, which provides the setting for an early section of the film before being abandoned – the narrative is steered onto a new path before things ever have a chance to grow stale.

In one such instance, the posse is made to stumble across a procession for a Yamana fire festival, where they seek camouflage among the many locals also laden with firewood. If the turn of events seems overly convenient, it is likely to be offset by the sequence that follows – one of Kurosawa’s finest. That night, a boisterous crowd has gathered to sing, chant and dance around a bonfire. The peasants, being unable to toss their wood into the flames like everybody else, quickly arouse suspicion. Enter Rokurota: he wrenches the cart from their grasp, hurls the load into the fire, and orders them to join the festivities if they want to live. ‘Dance!’, he roars, as he marches into the crowd like the warrior that he is. With no choice, Tahei and Matashichi do just that, flapping their arms while the treasure burns before their tearful eyes. Princess Yuki plays her part too – only with far more gusto. Turning and gliding this way and that, she more than holds her own among the revellers, and her hitherto anxious face transforms into something resembling a smile. It’s a giddy, moving sequence in which the social and moral boundaries that so often define (and confine) Kurosawa’s characters – between rich and poor, men and women, good and bad – briefly dissolve altogether.

More drama will unfold, and more blood will be spilled thereafter, but this sequence offers the clearest indication that The Hidden Fortress is, in the end, a hopeful fiction bordering on fantasy – one in which we suspect everything will work out just fine for this motley crew. Just as it stands as a brief anomaly within the darkest stretch of Kurosawa’s career, the film also feels like a slice of optimism carved from a harsh and unforgiving era: a moment of respite in an ugly world, where bad men can still come good.