White Pigs and Black Pigs, Wild Boar and Monkey Meat: Cannibalism and War Victimhood in Japanese Cinema

The following is an Accepted Manuscript version of a book chapter in (In)Digestion in Literature and Film: A Transcultural Approach (edited by Serena J. Rivera and Niki Kiviat), published by Routledge in May 2020.

Introduction

Before its belated release in Japan, Angelina Jolie’s World War II drama Unbroken (2014) attracted a controversy which made international headlines. The film—based on Laura Hillenbrand’s biography of American veteran Louis Zamperini, an ex-Olympic runner and a prisoner of war to the Japanese—drew the ire of rightwing Japanese nationalists who accused the director of misinformation and racism, with many taking particular offense at a section of the book describing how Allied prisoners were “beaten, burned, stabbed, or clubbed to death, shot, beheaded, killed during medical experiments, or eaten alive in ritual acts of cannibalism” (Hillenbrand 319; emphasis added). An online petition to prevent the film’s exhibition attracted 10,000 signatures. It declared that “there is no custom of cannibalism throughout Japanese history” and redirected attention to American atrocities against Japanese civilians during the war: “the indiscriminate bombing of Tokyo, Nagoya and Osaka, to begin, and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—and that’s not everything” (“Withdraw the production”; my translation). Toho-Towa was pressured into delaying the film’s distribution indefinitely and it was eventually shown on a single screen in Tokyo by an indie distributor, one year after its global release.

The film’s objectors turned out to be misinformed themselves. Unbroken depicts war crimes perpetrated by sadistic Japanese soldiers against Allied prisoners, but cannibalism, the sorest point of contention, was nowhere to be seen.[1] Nevertheless, the controversy revealed how the issue of war cannibalism can strike a nerve seven decades after Japan’s surrender, having been absorbed into broader debates surrounding the competing narratives and ideologies about Japan in the Pacific War. In recent years, scholars and commentators within and outside Japan have argued that a victim consciousness or mentality (higaisha ishiki) took hold in the nation in its postwar years, through which Japanese came to see themselves primarily as victims, rather than aggressors, during the war—an inwardness which “led most Japanese to ignore the suffering they had inflicted on others” (Dower, Embracing Defeat 29), and particularly the “victims of Japanese aggression [ . . . ] in Asia” (Shimazu 101). Although the Unbroken controversy revolved around an outburst of nationalist sentiment (expressed mostly online) and thus should not be mistaken for a typical Japanese standpoint on the war, the efforts to suppress the film appeared consistent with a narrative in which Japan denies or deflects responsibility for its wartime actions and claims the status of victim.

However, if we were to look at the handful of Japanese films which have actually tackled the issue of war cannibalism, it is possible to see that they engage with notions of victimhood in ways far more complex than is suggested by this narrative. Stories of war cannibalism, in these films and elsewhere, sit uneasily within the discourse of Japanese victimhood because the line between victim and perpetrator is often ambiguous or exists on multiple fronts. Depending on the context, victim status can be spread widely, and even a soldier who practiced cannibalism may be perceived to be a victim (his hand was forced by a brutal military system that abused and abandoned its own soldiers, and he must endure the psychological torment of committing cannibalism), a perpetrator (he committed a reprehensible and inexcusable act), or both simultaneously (he committed a horrific act but had little choice, and must suffer the consequences). As such, these films are well equipped to respond to historian Tanaka Yuki’s call to examine wartime Japan “as aggressors and as victims at the same time” (6).

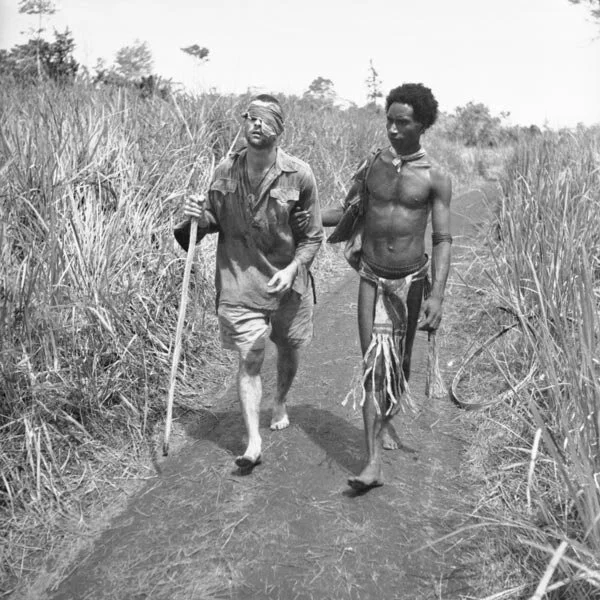

This ambiguity and multiplicity is entirely absent from the standard opposing perspectives of Japanese war cannibalism. The Japanese perspective tends to consider Japanese soldiers as the principal victims—in the rare event that the topic is considered at all, insofar as cannibalism remains a shameful taboo which has “long been confined to rumor” (Tanaka 114) and represented only by a small number of veterans’ memoirs, novels and films. Meanwhile, the standard perspective of ex-Allied nations is to regard cannibalism as an extension of Japanese military atrocities, whereby the principal victims are Allied soldiers and prisoners of war. While they focus predominantly on the experience of Japanese soldiers, Japanese films about war cannibalism diverge from this opposition and compel us to consider the very notion of war victimhood—not merely who the victims and perpetrators might be, but where the line between them begins and ends, or if such a line can be drawn at all. Their examination of war is predicated on using cannibalism to blur the distinction between victim and victimizer. Indeed, the historical circumstances surrounding cannibalism during the Pacific War suggest that the victim/victimizer binary is wholly inadequate. Japanese soldiers belonged to an army that victimized millions of others, many became victims themselves through their abuse and abandonment by that same army, and the acts of cannibalism which often resulted could confound distinctions of victimhood in themselves. After a remarkable succession of victories following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese military campaign just as quickly became an unmitigated disaster, a series of decisive defeats which remain virtually unprecedented. By the time the Allied blockade severed all supply routes in 1943, Japanese soldiers scattered throughout the Southwest Pacific region had been all but deserted by their government. Of the 1.74 million Japanese military deaths in the Pacific War, it is estimated that two thirds were due to illness and starvation rather than combat (Dower, War Without Mercy 448). In unforgiving tropical conditions for which they were completely unequipped, troops were decimated by disease and scavenged for rats, lizards, insects and plants to survive—all while being forced to flee, or suicidally fight, the advancing Allied forces. The resulting acts of cannibalism committed by Japanese troops—against enemy soldiers, prisoners of war, civilians, and each other—were among the worst of the Pacific War’s litany of horrors.

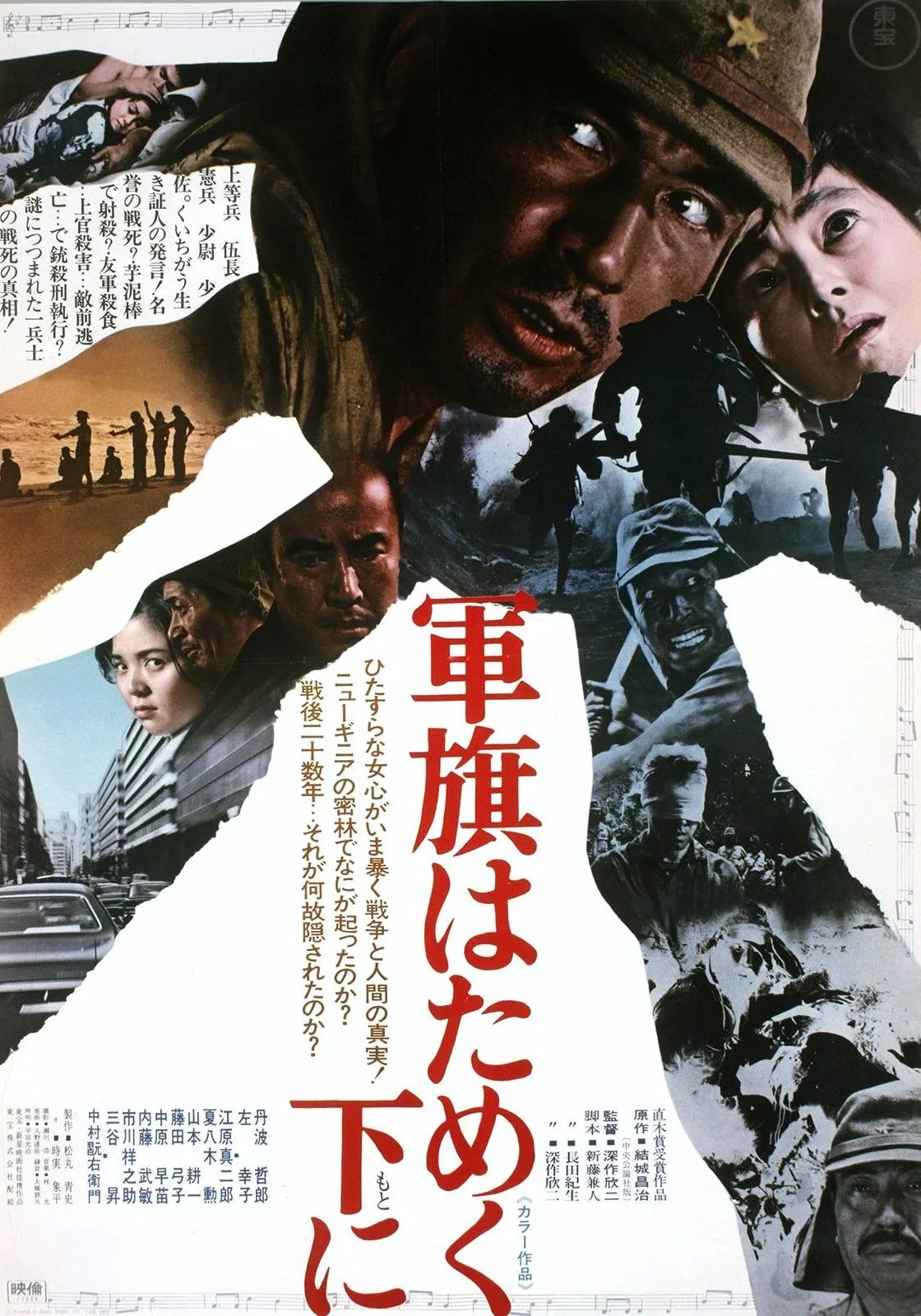

In this chapter, I focus on four Japanese films which foreground war cannibalism and examine the complexities of its victimhood. Ichikawa Kon’s Fires on the Plain (Nobi, 1959) and Tsukamoto Shinya’s phantasmagoric 2014 remake (both are adapted from Ōoka Shōhei’s 1952 novel) are set in the disastrous final phase of the war in the Philippines, and frame cannibalism as a moral choice faced by a protagonist whose morality is fast slipping away. Fukasaku Kinji’s Under the Flag of the Rising Sun (Gunki hatameku moto ni, 1972; based on Yūki Shōji’s 1970 novel) and Hara Kazuo’s documentary The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On (Yukiyukite shingun, 1987) are set decades after the war and look back at acts of cannibalism during the catastrophic New Guinea campaign, where death was virtually guaranteed for the Japanese soldier. While there are some other notable Japanese films relating to war cannibalism, such as Shindo Kaneto’s Ningen (1962), Kumai Kei’s Luminous Moss (Hikarigoke, 1992) and Matsui Minoru’s documentary Japanese Devils (Riben Guizi, 2001), the four films I have chosen are those which address cannibalism most directly as a central theme, and which are concerned with Japanese war experiences in foreign countries where cannibalism was most prevalent.

In cinema, cannibalism has long been aligned with the horror genre where the line between victim and perpetrator tends to be clearly delineated. No such delineation can be found in these four works and none qualify as horror films, but they share in common a reliance on the fundamental capacity for cannibalism to evoke horror; if war is hell, then cannibalism is readymade to prove that war is hell. Yet in these films, cannibalism extends well beyond a theme, image or narrative device used to evoke horror or express antiwar sentiment. While they demonstrate a fascinating diversity of approaches and attitudes, they all engage with the horrors of cannibalism to consider what the war meant, how it ought to be remembered, and why defining victimhood in such extraordinary circumstances can often be an elusive pursuit.

The Choice of Cannibalism: The Fires on the Plain Films

Of the handful of Japanese films which foreground war cannibalism, Ichikawa’s Fires on the Plain is the best known. In the film, Private Tamura (Funakoshi Eiji), stricken by tuberculosis and abandoned as a burden by his own regiment, wanders aimlessly through the Philippine island of Leyte where dead and dying Japanese soldiers litter the landscape. As his mental and physical states deteriorate, Tamura encounters other troops who have become insane from hunger and disease, and have resorted to theft, murder and cannibalism to survive. Tamura is not, however, merely a victim or witness to the horrors of war. When a young Filipino couple stumbles across him in a village, he kills the woman in a panic after she begins to scream, then attempts to kill her partner as he flees (only a jammed rifle saves him). Later, in the jungle, he runs into Nagamatsu, a young private whom he camped with earlier in the film, and Yasuda, an injured older private who exploits Nagamatsu as a servant for his own survival. The two men have been surviving by bartering tobacco leaves to other survivors for food, and subsisting off “monkey meat,” which Tamura is offered to eat but is unable to chew as it causes his teeth to fall out. Tamura soon confirms his suspicion that the meat is human flesh; under Yasuda’s unofficial command, Nagamatsu has been hunting Japanese soldiers for them to eat. The relations between the two men eventually turn sour, and Nagamatsu murders Yasuda and devours his flesh. Revolted by his cannibalism, Tamura kills Nagamatsu, in what registers equally as a punishment and a mercy killing. At the end of the film, Tamura approaches a group of Filipino farmers to surrender and is shot dead.

Fires on the Plain expresses its antiwar stance through an almost exclusive emphasis on Japanese victims, of both cannibalism (Japanese soldiers are the only ones to be cannibalized) and the war more generally. This is so despite the film’s setting of the Philippines—the site of so many well-known war crimes, rather than Japan, where so many films about Japanese victimhood are set—suggesting a willingness to interrogate Japanese war aggression. However, the circumstances of the narrative impede this interrogation from taking place. Here, the disintegrated Japanese Army is constantly on the retreat; in the rare instances when combat occurs in the film, Japanese soldiers become victims of a lopsided slaughter, attacked from afar by an enemy that can barely be seen, let alone fought. Additionally, Tamura’s refusal of cannibalism at the expense of his own survival, and his killing of a man who partakes in it, suggest a noble victim who rejects both moral complacency and the victimization of others. His death at the end of the film, by Filipinos—who represent a population which was relentlessly victimized by the Japanese Army—seems to underline his victimhood in the most literal sense.

Predictably, and although it has a long reputation as one of the great antiwar films, Fires on the Plain has also received criticism for espousing the discourse of Japanese victimhood described above. According to Erik R. Lofgren, this espousal is most apparent in the changes made from Ōoka’s source novel. In the novel, Tamura is not killed but rather captured by Filipinos, and he relates his story via flashback from a mental hospital where he admitted himself after experiencing memory loss and a putative bout of insanity: a structure which establishes “a necessarily ambiguous space for the ethical evaluation of his past actions” (267). More significantly, Tamura knowingly eats human flesh in the novel but refuses to do so in the film, a change which for Lofgren reflects “an ideological shift toward an increasingly hegemonic national victim consciousness [and] by broader implication, suggest[s] that Japan has nothing for which to apologize” (268). For Chuck Stephens, both Fires on the Plain and Ichikawa’s earlier antiwar film, The Burmese Harp (Biruma no tategoto, 1956), “endeavor to delineate a universalist depiction of victimization during wartime, even as they, through the suppression of certain inconvenient historical realities, focus almost exclusively on the victimization of the Japanese.” The “inconvenient historical realities” in the case of the war in the Philippines include the brutal actions of Japanese soldiers towards the native population and Allied prisoners of war, manifesting in “forced-labor camps, sexual slavery, the notorious Bataan Death March [ . . . ] and the slaughter of some one hundred thousand civilians by fleeing Japanese forces from the city of Manila alone” (Stephens). Most of these atrocities fall outside the narrative parameters of Fires on the Plain, having occurred elsewhere in the Philippines or well before the late stage of the war depicted, and with the sole exception of the woman’s murder, Japanese atrocities remain mostly subtext. Perhaps the most significant suppression, as it relates directly to a central theme of the film, is of the documented fact that cannibalism was perpetrated by Japanese against combatants and civilians from various other nations, and often with the direct endorsement by officers.[2]

While it may be unrealistic to expect a single film to incorporate the full spectrum of atrocities that Stephens describes, it holds true that these atrocities are barely addressed in the film, and that the victimization of Japanese is emphasized well over that of others. Yet at the same time, it is through the narrowness of its focus that the film’s particular ideas about cannibalism and victimhood are able to be articulated. Because Ichikawa continually emphasizes Tamura’s immediate experiences, the camera rarely strays away from him to offer a wider context for the war. This closeness, coupled with the scarcity of both fellow survivors and enemy combatants within the narrative, creates a vivid atmosphere of isolation and claustrophobia whereby Tamura’s physical and mental degradations become magnified. For Tamura, the enemy becomes blurred in more ways than one as the film progresses: the enemy soldiers can barely be seen (he also does not know whether the Filipinos he encounters are neutral civilians or enemy guerrillas), while the Japanese soldiers, despite sharing the same tongue and wearing the same uniform, can no longer be trusted and may be harboring a murderous intent driven by hunger. Within these narrowed visual and narrative parameters, the threat shifts palpably from a traditional external enemy to that from within the group, or what is left of it, and paves the way for Japanese soldiers to turn on each other. Consequently, distinctions between victim and victimizer become immaterial by the end of the film. Nagamatsu and Yasuda, for example, become so grotesque and unsympathetic that trying to distinguish who the victim is would be a fruitless exercise; the depravity of each character has negated the other.

As such, the film is much less concerned with depicting the scope of the war in the Philippines as it is with emphasizing how disorganized, dehumanized and depraved the Japanese Army had become. And all of this is seen to be a direct result of the army’s brutal repression and victimization of its own soldiers, as stressed from the film’s opening scene when Tamura is physically and verbally abused by his commanding officer and urged to commit suicide. In turn, cannibalism becomes a tangible consequence of, as well a metaphor for, this repression and victimization. In their master-servant relationship, which comes to resemble that of an officer and subordinate despite their equal rank, Yasuda asserts his dominance over the younger Nagamatsu and sends him away to do all the dirty work on his behalf. Earlier, when Tamura encounters another group of two privates and a sergeant, the latter reveals that they committed cannibalism in New Guinea, and warns—perhaps jokingly—that they might eat him too. Tamura’s possession of salt prevents the threat from being realized, but the men’s attitudes towards him as a lone outsider of low rank, and the compliance of the two subordinates to the sergeant’s authority (the sergeant looks far healthier and better fed, and later confiscates their portions of salt for himself), suggest that Tamura would likely be the first to be killed and eaten should the order be given.

Cannibalism is thus always shown or implied to occur within the context of military hierarchy, regardless of whether the hierarchy is official (as is the case with the three soldiers) or self-imposed (Yasuda and Nagamatsu). Cannibalism is sanctioned by superiors, and victims are chosen based on the observation—and in Nagamatsu’s murder of Yasuda, the eventual subversion—of an established rank. Tamura’s status as a lone soldier who no longer has anyone to answer to (but who himself is shown to be both victim and victimizer) allows us to observe the dynamic in which their cannibalism occurs. In this way, the film demonstrates that militarism and cannibalism are inexorably linked: the latter is an articulation of the former. Although criticisms about the film’s historical elisions remain valid, its narrowed focus must also be considered as a sincere attempt to examine war circumstances which were specific to the Japanese—one which, in turn, may shed a greater light on the Japanese victimization of others.

Although it adheres to a similar plot, Tsukamoto’s 2014 remake produces altogether different effects and meanings. In the film’s press kit, Tsukamoto suggests that his primary aim was to re-evoke the horrors of war for a contemporary Japanese audience, warning of the risk that “the idiocy of war will be forgotten, with so few left who have witnessed its horrors. The price of those 70 years of peace is a tendency to look away from death. As a result we have become collectively fearful of anything ‘dirty’” (10). Because of this “widening distance” between the war and the present, writes Mark Schilling, the film represented for its director “a last chance to make the reality of war undeniable and unforgettable.” Tsukamoto upholds this commitment by “dirtying up” the film’s source material significantly, amplifying the visceral horrors associated with cannibalism and infusing the film with nightmarish details which do not exist in the original film or novel, or which far exceed their equivalents. Formally speaking, the handheld camera sways erratically this way and that, the lighting scheme is deliberately overstated and artificial, jump cuts abound, and the cheap video aesthetic is accentuated by overexposed images and an oversaturated color grade. The enemy have also become invisible altogether from combat scenes, which are now mostly conveyed by a series of offscreen sounds, fragmented images and quick disorienting cuts, with a more pronounced emphasis on violence.

The cumulative effect of these excesses is an intense subjectivity which is not present in the original film. Tsukamoto’s Fires on the Plain is a hallucinatory nightmare of images and sounds experienced by its protagonist (played by Tsukamoto himself), in which narrative and context become a distant concern. Tamura is consistently underlined as a witness by an abundance of closeups of his face, intercut with reverse-shots of the horrors unfolding around him. Point-of-view shots, long dissolves, abstract images of the landscape, and visual and auditory flashbacks also suggest his anguished mental state in a way that the screenplay does not. Tamura’s role in the earlier film as a protagonist through whose eyes we experience the war, and who retains a degree of sympathy by being shown grappling with the moral consequences of his actions, becomes destabilized here because he, like most of the other soldiers, seems to be constantly teetering on the edge of sanity.

These excesses also contribute to the blurring between victim and victimizer, through which Tamura appears to have an out-of-body experience and commit savage crimes. In the scene of the woman’s murder, Tamura initially assures her, “I won’t kill you,” before she screams and Tsukamoto starts cutting rapidly back and forth between the two characters. Tamura shouts the words repeatedly as his panic grows, and Tsukamoto introduces barking dogs on the soundtrack to amplify the mounting confusion. As the editing gathers speed and momentum, violence begins to feel inevitable, as though it will be forced by the pressure building through the film’s style rather than by narrative logic or motivation of character. This seems to be confirmed when, in the film’s most problematic moment, Tamura shoots the woman dead then looks down at his rifle in shock—as if it were not his own finger that pulled the trigger but some other mysterious force which came over him. The outcome of the scene is the same as in the original film, but here the responsibility for the murder has been ambiguously deflected.

A similar displacement of responsibility can be seen in the film’s treatment of cannibalism. A major difference from Ichikawa’s film, and marking a return to Ōoka’s novel, is the fact that Tsukamoto’s protagonist eats human flesh—an act which would appear to refuse him victim status, and reinforced by the fact that he is captured by Filipinos at the end of the film rather than be killed by them. Tamura eats human flesh twice: when he wakes from exhaustion and is fed a piece of dried meat by Nagamatsu (before its origin is revealed), and when he narrowly escapes a grenade blast and consumes a small piece of flesh that lands on his shoulder (it is unclear whether the flesh is from his own body or a nearby corpse). The murder and cannibalism of Yasuda towards the end of the film remains, but is rendered far more gruesome. After the protracted mutilation of Yasuda’s corpse, Nagamatsu, mouth agape and covered in blood and flesh, stares at Tamura with a ghastly expression before he too is killed.

However, this and the other scenes of cannibalism barely stand out because the copious other horrors depicted in the film operate mostly on the same, heightened register. Due to the film’s constant stream of excesses, all instances of cannibalism lose their accents, becoming subsumed within a procession of horrors which are afforded similar or equal emphasis in their stylistic treatment and position within the narrative. Tsukamoto homogenizes the horrors of war, strips them of their context, and also simplifies the ethical considerations relating to cannibalism; indeed, he has stated, “What’s more important than the theme of an individual’s conflict over whether or not to eat human flesh is the depiction of the horrors of war in general” (Walkow). The film creates and maintains an extreme impression of war, and this is achieved in part by inadvertently downplaying—rather than emphasizing—its greatest horror. Cannibalism becomes depoliticized and dislodged as a central theme; it is still there, to be sure, but the film no longer needs it in order to function.

Despite again focusing on the victimization of Japanese soldiers—much more intensely than in Ichikawa’s film—one cannot easily claim that the film chooses to prioritize it over the suffering of others, for distinctions of victimhood are made redundant once more. Such is the pure concentration of its focus: the Fires on the Plain remake strives for nothing beyond a relentless sensory experience of the chaos, violence, and trauma of war. Whether this strategy is effective or meaningful is a matter for debate, and questions remain about the relative absence of Japanese atrocities. But in Tsukamoto’s vision, cannibalism becomes an equal part of a tapestry of horrors to which none are immune; every soldier, without exception, becomes capable of theft, murder, and eating the flesh that Tamura refused in Ichikawa’s film.

Cannibalism in Hindsight: Under the Flag of the Rising Sun and The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On

Fukasaku’s Under the Flag of the Rising Sun is set twenty-six years after the war and begins with Togashi Sakie’s (Hidari Sachiko) annual visit to the Ministry of Welfare to apply for a war widow’s pension. Her application is rejected yet again; she is ineligible to receive benefits because her husband, Sergeant Togashi Katsuo (Tanba Tetsurō), was executed in New Guinea for desertion, although no record of a court martial exists. The real reason for her visits, however, is simply to learn the truth, and on this occasion her pleas are heard by a sympathetic bureaucrat who hands her the names of four veterans from her husband’s regiment. Sakie tracks down each of the men (she also visits a fifth veteran after a tipoff) and they recall contradicting accounts of her husband’s final days. These are depicted in wartime flashbacks of varying reliability, ranging from stories of a heroic man who died valiantly in battle, to a deserter who murdered and cannibalized other Japanese soldiers.

Fukasaku employs a vast array of techniques to depict this fragmented and ambiguous narrative, through which the concept of truth becomes fluid and distinctions between victim and victimizer become unstable. These techniques—including the use of color and black-and-white cinematography, freeze frames, archival images, graphics and captions—become increasingly sophisticated as the film progresses. For example, captions and archival images are used to provide historical context towards the start of the film, but are later used to illustrate portions of the veterans’ accounts as if corroborating them, even though most of the accounts turn out to be rife with misinformation and lies. Similarly, Fukasaku initially uses black-and-white and color cinematography in a conventional manner—to denote the past and the present, respectively—but later shifts between them when only a negligible chronological shift has occurred, or to punctuate dramatic (usually violent) moments during flashbacks. In this fashion, Fukasaku constantly overlaps or collapses distinctions between past and present, fact and hearsay, and objective and subjective representation.

Although the film again focuses mainly on the plight of stranded and starving Japanese soldiers, Under the Flag of the Rising Sun transcends the linear and narrow narrative parameters of the Fires on the Plain films via its fragmentary structure, through which a wider range of victims and victimization is examined. The abuse of Japanese soldiers by their superiors is predominant, but there are few outright victims in the film—none more so than Sergeant Togashi, who is conveyed equally as victim and perpetrator across the veterans’ stories. Tellingly, Fukasaku rationalized Togashi’s characterization in the context of Japanese war victimhood:

Even the author of the original novel wasn’t happy that I had chosen from among his many characters a central character who was guilty of murdering his superior officer, rather than someone who was purely a victim of the state. But I did not want to add my film to the list of war films made from a victim mentality. Although the film was well reviewed by Japanese critics, I think it’s revealing that not a single one of them mentioned that the lead character murders his superior officer. (qtd. in Hoaglund)

Other than through this central character, Fukasaku’s desire to avoid a victim mentality is most apparent in the foregrounding of Japanese war crimes. The “inconvenient historical realities” that Stephens accuses Ichikawa of sidestepping in Fires on the Plain manifests here in the massacre of New Guinean farmers and the botched beheading of an American prisoner, and reverberates in a postwar scene where ex-military Police Sergeant Ochi rapes his wife in a fit of rage.

Cannibalism has a brief but vital role within this multifaceted narrative, crystallizing as a key theme through which victimhood is explored. In the first instance of cannibalism, Ochi tells Sakie about the execution of a sergeant who may or may not have been her husband. In the corresponding re-enactment, Togashi emerges alone from the jungle and approaches a group of starving soldiers with “wild boar meat” to trade for salt. A suspicious private follows him back into the jungle but does not return, and when Togashi reappears days later with a fresh supply of meat, he is confronted and confesses to the soldier’s murder. In the second instance of cannibalism, ex-Private Terajima admits to having survived by eating the flesh of a murdered officer, after being left behind to die in the jungle by his comrades (including Togashi). The context of cannibalism in these two accounts is markedly different, and Fukasaku pronounces the differences. Ochi’s account frames cannibalism as an extension of the Japanese Army’s degeneracy, particularly as it follows another veteran’s description of the level of hunger and desperation in New Guinea: in the earlier scene, soldiers are shown fighting and scrambling over each other as they chase a rat, and Fukasaku freezes the image sporadically to show them tearing the animal apart with their teeth. On the other hand, Terajima’s account of cannibalism is handled with restraint. Fukasaku elides the act of cannibalism altogether and focuses instead on its moral implications, lingering on the veteran’s emotional state before and after. In Ochi’s account, cannibalism represents a murderous deed which reinforces the depravity of the starving soldiers; in Terajima’s, it is framed as a tragic outcome of his abandonment, and necessary and forgivable in the circumstances.[3]

It is significant that these two men are the only veterans that Sakie visits twice, upon learning that they were initially lying or omitting crucial details. It is eventually revealed that Terajima turned in Togashi and the other men to save himself from execution (albeit for a murder he did not partake in), and also harbored the shameful secret of cannibalism; Ochi, meanwhile, was directly responsible for Togashi’s illegal execution by pulling the trigger. How these men deal with their lies reflects contrasting notions of war victimhood and responsibility: Terajima takes responsibility for his actions and confesses despite being a victim himself, while Ochi, a victimizer, lays the blame on others and refuses to be held accountable. When Terajima comes clean to Sakie about his cannibalism and knowledge of her husband’s execution, he is quickly forgiven. Ochi, however, never confronts his lies; when Sakie visits him for the second time, she finds that he has taken his own life. She will never know if her husband had committed cannibalism like Ochi had claimed, but it seems highly probable that the story was concocted. Unable to forget or face up to his wartime actions, Ochi had likely turned Togashi into a murderous cannibal to justify his own role as executioner and deflect his war guilt.

The closing shot of the film severely undermines its commitment to refuse a victim mentality: a pile of skulls burning on a fire, set to a melodramatic musical score, over which a caption displays statistics of (only) Japanese casualties in the Pacific War. Despite this skewed ending, the film mostly cultivates a sense of uncertainty whereby questions of victimhood remain complex, fluid and ambiguous—and through which all soldiers become victims and victimizers, alternately or simultaneously, one invariably sustaining the other. While many details ultimately remain inconclusive, the film’s fractured style and structure maintain the possibility that everything told by the veterans may have occurred, if not necessarily in the way that they are told—as well as much worse. Just as it could be reasonably assumed that certain characters committed other crimes not depicted in the film, the harrowing realities of war, epitomized by cannibalism, are made to linger in the imagination beyond what the narrative is able to include. What we see and hear in Fukasaku’s film are but fragments of a small number of stories, which have been forced out into the open.

Many of the themes and insights of Under the Flag of the Rising Sun resonate in Hara’s The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, a controversial documentary which forms a fascinating companion piece to Fukasaku’s film. It takes place in the early 1980s and follows war veteran and dissident Okuzaki Kenzō, a survivor of the New Guinea campaign from which only thirty of the one thousand members in his regiment returned alive. Okuzaki has devoted his postwar life to attacking war values and bringing to justice Emperor Hirohito, whom he holds personally responsible for the war and describes as “the most cowardly man in Japan” as well as “a symbol of ignorance, irresponsibility and impossibility.” After observing Okuzaki’s various acts of political protest and civil disobedience in its first half hour, an intertitle introduces the film’s central mystery: two privates from Okuzaki’s regiment were allegedly executed in New Guinea by members of their own unit, weeks after Japan had surrendered.

With Hara and his film crew in tow, Okuzaki crisscrosses the country to question the surviving witnesses, most of whom are now elderly men living in relative anonymity. Arriving unannounced at their homes and workplaces with the camera already rolling, Okuzaki proceeds to interrogate, verbally abuse, and occasionally assault the men to obtain the truth. He sometimes brings two relatives of the deceased privates to coerce the veterans into confession, and when they later pull out of the film, he simply replaces them with substitutes (his own wife and a friend) to “play” the roles. These contentious scenes raise serious questions about the filmmaker’s own practice and ethics: his choice about when to observe and when to intervene, his influence in shaping what occurs in front of the camera, and his use of a protagonist whose sanity is frequently called into question.

The veterans’ responses to Okuzaki’s interrogations vary widely, but most share in common a profound unwillingness to bring up events which they have kept hidden for decades. Many of the men are deliberately obscure about their knowledge of the execution, some try to deflect the blame onto other veterans and even back to the victims, while others offer fragments of information or partial admissions of guilt but deny full responsibility by claiming only to have followed orders. As in Fukasaku’s film, there are numerous gaps, inconsistencies and lies in the veterans’ accounts, and many details remain vague. Yet Okuzaki and Hara steadily expose information about the level of hunger, desperation, and fraternal abuse in New Guinea, eventually leading to startling confessions about cannibalism. By the end of the film, the viewer is left with enough anecdotal evidence to surmise that the two privates were illegally executed, under trumped-up charges of desertion, likely so that they could either be cannibalized by their superiors or kept quiet about their knowledge of cannibalism.

Ex-medic Hamaguchi offers no resistance from the outset and volunteers staggering details about the execution and the extent of the cannibalism that occurred in New Guinea, including victims that are not Japanese. In the film’s first candid revelation of cannibalism, he describes how Japanese soldiers ate “white pigs” and “black pigs”—euphemisms for white Allied soldiers (likely referring to Australians and Americans) and black New Guinean natives, respectively—but not each other. Ex-Captain Koshimizu provides a somewhat different account when he suggests that victims were selected according to a racial hierarchy: eating “white pigs” was officially forbidden, but “black pigs” were permitted.[4] Later, ex-Sergeant Yamada contradicts both veterans when he insists that cannibalism was prohibited outright, even though this made little difference for he and the other starving soldiers: New Guineans were spared from becoming victims only because they were too quick to catch, so Japanese soldiers were cannibalized instead, with the “troublemakers and selfish ones” the first to be targeted. Although Okuzaki shows far more interest in the fates of Japanese soldiers, these conflicting accounts nevertheless form a vital record confirming the pervasiveness of cannibalism towards the end of the war, and the breadth of victims that it entailed. They also encompass the varying postwar perspectives of cannibalism, which range from regarding it as a desperate food source (and not necessarily involving murder), to an atrocity that was symptomatic of the Imperial Japanese Army’s violence and racism.

Although the film unequivocally “rejects the notion that the Japanese were only victims” (Ruoff & Ruoff 42–43), its view of war victimhood is deeply complicated. Indeed, Okuzaki himself is largely unconcerned with identifying victims and perpetrators, as he seems to understand that Japanese soldiers needed to resort to cannibalism if they were to survive the final stages of the New Guinea campaign (he was spared this experience only because he was captured earlier). His quest is driven less by justice—for the most part, he does not seek punishment and is wholly dismissive of the law—than by a basic desire for each man to speak openly about the war and, when required, accept individual responsibility for their actions during it. Regardless of their crime or their professed level of guilt, Okuzaki essentially forgives the veterans when he sees that they are being forthright, or once they offer an apology or some admission of responsibility.

Otherwise, Okuzaki’s volatile behaviour and the veterans’ wavering responses may throw the viewer’s sympathies into disarray. Many of the veterans divulge harrowing deeds and demonstrate lingering wartime attitudes in their denials, obfuscations, and refusals to admit guilt or responsibility; some are revealed to be perpetrators in the most prosaic sense. Regardless, it is at times difficult not to feel for the elderly men as they are harassed, humiliated and assaulted by Okuzaki in front of their confused families and Hara’s unflinching camera. Furthermore, several of the veterans claim victim status at some point to justify their actions (or justify not discussing them), as does Okuzaki himself. Despite seeing himself as a victim of both the wartime and postwar political establishments, and exuding a peculiar charm for much of the film, Okuzaki is also a fanatical, violent, and self-righteous victimizer, throughout the film and beyond it. His onscreen violence and criminal history—including various acts of civil disobedience, but also the murder of a real estate broker for which he spent a decade behind bars—attest to this fact, as does the revelation at the end of the film that he was sentenced to twelve years in prison for attempted manslaughter after the production finished.[5] Through its unnerving protagonist, and more than any of the films discussed in this chapter, The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On reflects the fluidity and reciprocal nature of war victimhood—and it does so always whilst remaining rooted in the historical present.

Despite the film’s unassuming observational style, Hara is no mere observer of the events depicted, and his own participation plays a major role in confounding received notions of victimhood. Outside of the film, Hara has freely admitted to a degree of collaboration with Okuzaki and describes himself as “not the type of director to shoot something just happening [ . . . ] rather I like to make something happen” (Ruoff 108).[6] It was Hara, for example, who initiated Okuzaki’s investigation in the first place by alerting him to the possibility that the murder of the privates was related to cannibalism (Marks 125). Paradoxically, Hara’s presence in the film can be felt most strongly when he seems absent. When Okuzaki trespasses into a veteran’s home to attack him for evading questions, or assaults another frail veteran who has recently undergone surgery, the viewer may feel ambivalence or even contempt towards Hara as he continues to film and refuses to intervene.

The disconcerting irony is that Okuzaki’s and Hara’s often dubious methods are effective. Their dogged pursuit inevitably produces new victims and victimizers, but truths emerge because they are forcibly extracted from the veterans, and because the director refuses to stop recording. Jeffrey and Kenneth Ruoff write that the revelations of cannibalism in the film eventually “fulfil a cathartic function for veterans, victims, relatives and viewers” (34). But perhaps more important than what is revealed is how it is revealed, and what is not revealed at all. For what the film shows most powerfully is the disturbing extent of war denial—the act of forgetting—and the equally disturbing extent of what it takes to remember.

Conclusion

Insofar as the acts of cannibalism they show or allude to focus almost exclusively on Japanese victims, these films align with the standard Japanese perspective of war cannibalism described towards the start of this chapter. This is not to suggest, however, that they embrace the discourse of Japanese war victimhood or prioritize the lives of Japanese over those who suffered immensely at their hands. If it is a matter of obtaining equivalence between representations of Japanese as victims of war and as aggressors against peoples of other nations, these films are severely restricted by virtue of their specific focus and settings. The situations of war they depict are highly unusual, in that almost all of the violence committed is not by members of one nation against another—as is the custom in both war and war films—but against each other. Yet even within this narrow context, these films make a concerted effort to resist, or outright reject, allusions that Japanese were simply victims. Although there is relatively little room to maneuver within their conventional linear narratives, the Fires on the Plain films offer a context for war cannibalism that goes beyond survival, presenting cannibalism and militarism as deeply intertwined. In the case of Under the Flag of the Rising Sun and The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, the act of looking back at wartime cannibalism becomes an object of inquiry in itself; the unsettling ambivalences which echo across these two films elucidate, rather than obfuscate, the extent of Japanese atrocities.

While all of these films differ radically in their form, methods and scope, they share a commitment to using cannibalism to explore a complex spectrum of war victimhood. James J. Orr suggests that the standard victim narrative in postwar Japan deflects war responsibility and places “Japanese people on the high ground of victimhood; the role of victimizer was assigned to the military, to the militarist state, or to the vaguely defined entity called simply ‘the system’” (3). These films, which focus almost exclusively on members of the military, show how such suggestions can be insensitive to the realities and nuances of the war situation. The people in these films are often victims and perpetrators alternately, or in some cases, simultaneously. They remind us that war victimhood can be assigned in many directions, and that distinctions between victims and victimizers may swap, shift, oscillate and dissolve according to the context; indeed, these films refute the very notion of a “standard” perspective of war.

In a scene in The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On, Okuzaki explains the reasons behind his provocative actions in the plainest possible terms: “To reveal the misery of the war will keep the world free from war.” At their most basic level, these antiwar films follow the same hope and strive for the same goal. The taboo of cannibalism is unearthed, framed, and showcased in all its misery and ugliness. It is a corrective for any representations of war which show it as anything other than the worthless slaughter that it is.

Works Cited

Dower, John W. War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. Pantheon Books, 1986.

---. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. W.W. Norton & Company, 1999.

Fukasaku, Kinji, director. Under the Flag of the Rising Sun. Toho, 1972.

Hara, Kazuo. Camera Obtrusa: The Action Documentaries of Hara Kazuo. Kaya Press, 2009.

Hara, Kazuo, director. The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On. Facets, 1987.

Hillenbrand, Laura. Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption. Random House, 2010.

Hoaglund, Linda. Audio commentary. Under the Flag of the Rising Sun. Dir. Fukasaku Kinji. 1972. Home Vision Entertainment, 2005. DVD.

Ichikawa, Kon, director. The Burmese Harp. Nikkatsu, 1956.

---. Fires on the Plain. Daiei, 1959.

Iriye, Akira. “The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On.” The American Historical Review, vol. 94, no. 4, 1989, pp. 1036–1037. doi: 10.2307/1906597.

Jolie, Angelina, director. Unbroken. Universal Pictures, 2014.

Kumai, Kei, director. Luminous Moss. Herald Ace, 1992.

Lofgren, Erik R. “Christianity Excised: Ichikawa Kon’s Fires on the Plain.” Japanese Studies, vol. 23, no. 3, 2003, pp. 265–275. doi:10.1080/1037139032000156342.

Marks, Laura U. “Hara Kazuo: ‘I am very frightened by the things I film’.” Spectator, vol. 16, no. 2, 1996, pp. 123–131.

Matsui, Minoru, director. Japanese Devils. Japanese Devils, 2001.

Ōoka, Shōhei. Fires on the Plain. Translated by Ivan Morris, Tuttle, 1951.

Orr, James. The Victim as Hero: Ideologies of Peace and National Identity in Postwar Japan. University of Hawaii Press, 2001.

Ruoff, Jeffrey, and Kenneth Ruoff. “Japan’s Outlaw Filmmaker: An Interview with Hara Kazuo.” Iris: A Journal of Theory on Image and Sound, no. 16, Spring 1993, pp. 103–113.

---. The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On. Flicks Books, 1998.

Schilling, Mark. “A second look at bloody WWII novel ‘Fires on the Plain’.” The Japan Times, 22 Jul. 2015, www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2015/07/22/films/film-reviews/second-look-bloody-wwii-novel-fires-plain/#.XHS3wpMzbOQ. Accessed 7 Jan. 2019.

Shimazu, Naoko. “Popular Representations of the Past: the Case of Postwar Japan.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 38, no. 1, 2003, pp. 101–16. doi:10.1177/0022009403038001966.

Shindo, Kaneto, director. Ningen. Art Theatre Guild, 1962.

“Sourcing Misinformation from Japan’s Right Wing.” The Point, 2015, http://newasiapolicypoint.blogspot.com/2015/01/sourcing-misinformation-from-japans.html. Accessed 1 Jul. 2018.

Stephens, Chuck. “Fires on the Plain: Both Ends Burning.” The Criterion Collection, 13 Mar. 2007, www.criterion.com/current/posts/473-fires-on-the-plain-both-ends-burning. Accessed 1 Nov. 2017.

Tanaka, Yuki. Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II. 2nd ed., Westfield Press, 1996.

Tsukamoto, Shinya, director. Fires on the Plain. Kaijyu Theater, 2014.

Tsukamoto, Shinya. “Director’s Comment.” Fires on the Plain Press Kit. Coproduction Office, 2014.

Walkow, Marc. “Interview: Shinya Tsukamoto.” Film Comment, 19 Feb. 2015, www.filmcomment.com/blog/interview-shinya-tsukamoto/. Accessed 1 Feb. 2019.

Wisnewski, J. Jeremy. “A Defense of Cannibalism.” Public Affairs Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 3, 2004, pp. 265–72.

“Withdraw the production and distribution of the film whose contents are contrary to the truth!” (事実に反する内容の映画の製作と配信を撤回すべき!) Change.org, www.chng.it/ZhxLfL8jRB. Accessed 1 Jul. 2018.