World Without a Map: The Flattening Perspective of Jennifer Peedom’s River

Originally published in Metro no. 213 (August 2022).

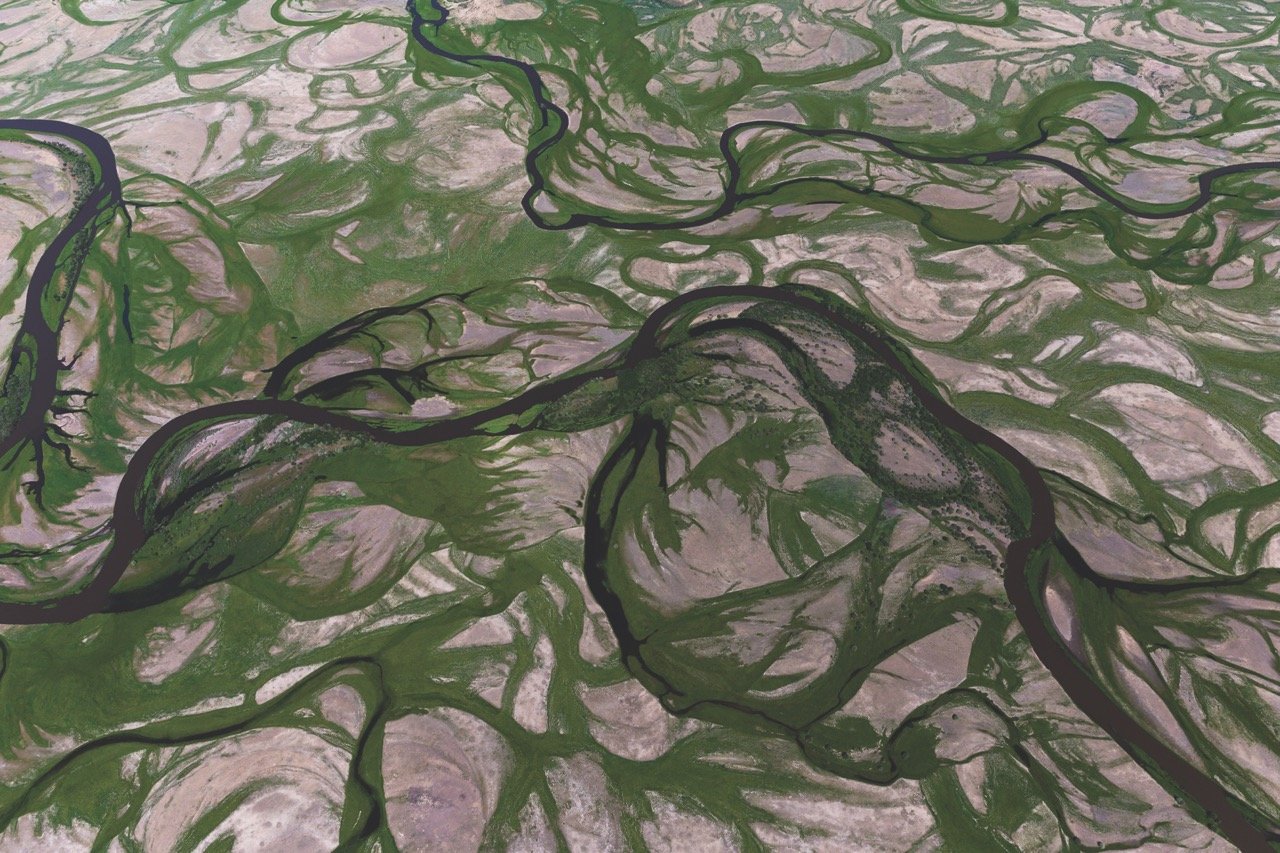

I was reminded of theme park rides in general – and ‘It’s a Small World’, specifically – when I watched Jennifer Peedom’s River (2021), a documentary that ruminates on the beauty, significance and vulnerability of the world’s rivers, and that the director describes as an ode to the ‘arteries of the planet’.[2] It’s an apt description of the interconnectedness of rivers and the myriad ways in which they sustain life; as Peedom’s film shows, these waterways do everything from nourishing ecosystems to providing drinking water and connecting civilisations via transport and trade. As it happens, arteries (or veins) are also what river systems resemble when viewed from above. River spends most of its running time doing just that: it drifts, glides, swoops and soars above and along all varieties of its namesake, mostly from the perspective of drones but also reaching as high as satellites in space. Though it sometimes lands on the ground and even plunges underwater on occasion, River is primarily an airborne film, a film of the twenty-first century.

More pertinent than spectacle, as far as my favourite childhood attraction is concerned, is the film’s global scope and pretensions to universality. River also embarks on an aquatic journey through the world, as it were, traversing a whopping thirty-nine countries in six continents over its seventy-five minutes. Interestingly, most of this coverage was achieved without the filmmakers ever needing to hop on a plane. With their ability to travel hampered by a nationwide COVID-19 lockdown, Peedom and co-director Joseph Nizeti were compelled to scour dozens of archives for material, and outsourced the bulk of the shooting to an informal network of nature cinematographers scattered around the globe.[7] Twenty-three cinematographers ended up contributing footage (for which five receive principal credit[8]), while archival materials were obtained from a total of sixty different sources ranging from personal media libraries to NASA satellite imagery. Peedom describes her role in the production as more akin to a conductor than a director,[9] and it’s easy to see why.

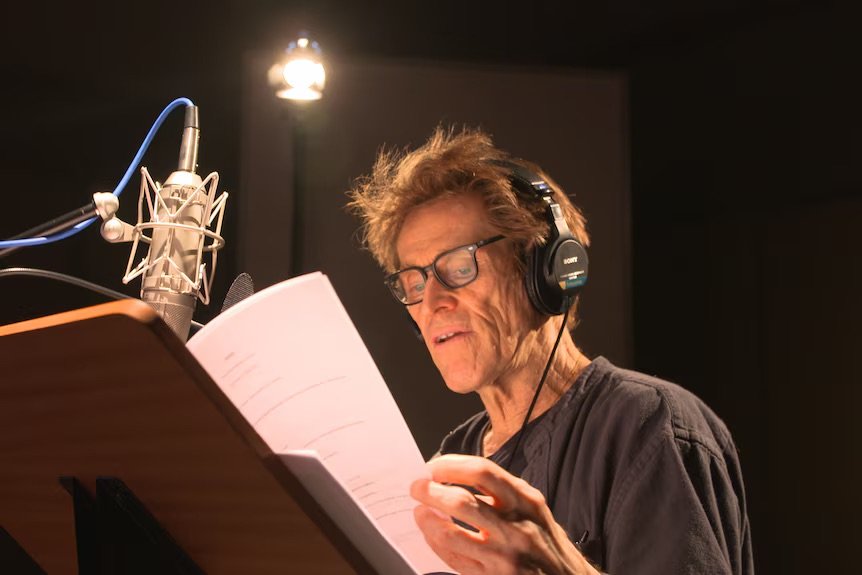

The voiceover occasionally relates information somewhat in the manner of a typical nature documentary. We’re told, for instance, that the largest dams have hoarded enough water from rivers to slow the planet’s rotation.[12] Mostly, it sticks to the task of exuding an all-encompassing admiration for rivers in prose laden with mystical overtones. Rivers are ‘wellsprings of wonder’ and ‘sources of human dreams’ that have ‘flowed through our lives like they have flowed through places’;[13] their ‘only purpose is to descend’, but they’re also ‘fickle and unpredictable’ and can help ‘make war and bring peace’, too. River’s voiceover takes the notion of a ‘voice of God’ narration to near-literal levels, and it comes as no shock that even the most ardent admirers of the film have found themselves allergic to it.[14]

Willem Defoe recording narration for River.

The film follows even more closely the template of Peedom’s Mountain (2017), which came hot on the heels of her award-winning Sherpa (2015) and holds the honour of the highest-grossing non-IMAX documentary ever released in Australia.[18] I’m not using ‘template’ in a flippant way here: there really is one, and River follows it almost to the letter, right down to its analogous running time and the fonts duplicated in the credits. The two films share the same main collaborators and were assembled from footage obtained through similar means; they both also open with a black-and-white prologue of an orchestra tuning up, and include comparable archival sequences that provide historical crash courses on their respective subjects. Tonally and structurally, they’re almost indistinguishable: swap out the mountains of Mountain for rivers and you’ll have a fair idea of what River entails. When rivers are eventually replaced by another landform, thus completing the final third of a trilogy that has already been hinted at,[19] it’s a safe bet that the same template will be applied once more.

Mountain (2017)

But as River showcases in abundance, it has become possible to capture the sheer, expansive scale of a river – or even an entire river system, even in a single shot – if the camera can get up high enough. The technology that can enable this with relative ease might be recent, but the trade-off is age-old: the higher or farther you get, the more abstract things become. At a certain elevation, rivers invariably flatten into a series of lines and shapes[20] – the kind of unusual, albeit gorgeous, sight that a bird or an astronaut might admire from above, far removed from what the rest of us plebs can see, hear, touch, smell or catch fish from at ground level. In any event, floating above the earth’s surface has hardly been a convenient option for most of cinema’s history – certainly not for documentaries. Which is why films have relied on a humbler, but tried-and-tested, approach when it comes to these waterways: travel horizontally rather than vertically, to see where the river doth flow.

Unfortunately, it proves to be an isolated example only. Once the sequence ends, the film slips into a comfortable routine of cherrypicking and jump-cutting between snippets of waterways, taken from anywhere and everywhere, the sum total of which is an amorphous concept of a river that is meant to encompass every single one of them. Beyond what is shown in a single shot, which is never held for more than a few impatient seconds, we rarely get to see a river flow. On the odd occasion that a river is followed for longer, its path is merely suggested by editing together fragments from downstream, as films have always done, or simply by stating it through the narration, as films have also always done. For all the splendour of its cinematography and the high-tech nature of its collaboration – both very much products of our time – the approach that River settles for is rather conservative and old-fashioned, and contains none of the revelatory power of that drone shot.

And yet being everywhere and knowing everything remains River’s guiding principle, which is further complemented by a narration that appears to address everybody. ‘As we have learned to harness the power of rivers, have we forgotten to revere them?’ Dafoe ponders in the film’s opening. If ‘we’ refers to all of humanity, then the simple answer might be that some of us have indeed forgotten and some of us haven’t, while some of us never revered rivers and likely never will. Although this sort of vague, universalist rhetoric is not uncommon, especially during times of crisis, River’s narration reminded me of a particular slogan that was repeated ad nauseam in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: ‘We’re all in this together.’ Spruiked by political leaders and parroted by common folk worldwide, this phrase initially seemed to contain some modicum of truth – that is, until it started popping up in marketing campaigns and people cottoned on to the fact that no, the pandemic is not in fact experienced by everybody in the same way.[21]

The Australian Chamber Orchestra performing a live score for River.

Many documentaries can be justly criticised for being too obsessed with information, but River suffers from exactly the opposite problem. In its dogged pursuit of the universal, the film in fact goes out of its way to efface information – or practically any sign of specificity whatsoever. We don’t learn the names of any of these rivers or in which countries they lie, just as we’re never told whom these people and cultures are that are frequently glimpsed in the images or alluded to in the prose. No signposts are provided, and no voice can be heard outside of Dafoe’s blanketing narration. Other than what we can deduce through our own general knowledge, we’re left entirely to our own devices.

This isn’t such a problem when the film focuses on admiring rivers, which it mostly does, but it becomes one when it attempts to press its environmentalist concerns. Like many documentaries worthy of the name, River aspires to do more than just admire its subject: it also issues a warning and encourages us to reflect on the consequences of human behaviour. ‘Look after the river and the river will look after you,’ the narration proclaims, thus voicing what might be considered the film’s key message. But in the absence of any meaningful context through which such a message can be understood and appreciated, let alone acted upon, it becomes diluted to the point of meaninglessness.

The film does appear to come up with one solution, however, and a very practical one at that. Having dedicated much of its middle section to the topic of dams and their environmental consequences, River culminates in a cathartic sequence of dam walls being blown open with dynamite. As Radiohead’s ‘Harry Patch (in Memory of)’ soars, biblical torrents of water are liberated from behind the concrete, releasing along with them all of the river’s nourishing silt that has been lying trapped and stagnant. Within the space of a few slow-motion images, dried riverbeds are invigorated and entirely new rivers are formed. Birds return to the sky in joyful formation; fish swim once more. While the desire to close a film like this with optimism is perfectly understandable, River’s finale presents cause and effect with such brute simplicity that it registers as nothing less than fantasy; moreover, like elsewhere in the film, the spectacle lulls you into a relaxed, politically disengaged trance. When the credits begin to roll soon after, one can be forgiven for thinking they’ve figured it all out: just blow up the dams and be done with it, already.

[2] Jennifer Peedom, in ‘Jennifer Peedom on Her Film River – An Ode to the Arteries of the Planet’, Uncommon Sense, 3RRR, 22 March 2022, available at <https://www.rrr.org.au/on-demand/segments/uncommon-sense-jennifer-peedom-on-her-film-river-an-ode-to-the-arteries-of-the-planet>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[3] Glenn Dunks, ‘Film Review: River Is a Visual Spectacle’, ScreenHub, 17 March 2022 <https://www.screenhub.com.au/news/reviews/review-river-documentary-1485203/>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[4] Tara Brady, ‘River: Poetic Exploration of the Planet’s Arteries’, The Irish Times, 25 March 2022, <https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/film/river-poetic-exploration-of-the-planet-s-arteries-1.4833337>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[5] Peter Bradshaw, ‘River Review: Spectacular Montage-doc Goes to Work on Gushing Waters’, The Guardian, 16 March 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/mar/16/river-review-jennifer-peedom-willem-dafoe>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[6] Jim Schembri, ‘Eco-doc River, a Lyrical, Visually Beautiful Ode to the Power and Fragility of Rivers That Mesmerizes – Despite an Unnecessary Narration’, 23 March 2022, <https://www.jimschembri.com/eco-doc-river-a-lyrical-visually-beautiful-ode-to-the-power-and-fragility-of-rivers-that-mesmerizes-despite-its-unnecessary-narration/>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[7] Peedom explains that budgetary limitations meant this collaborative approach would have been required regardless, though presumably to a lesser extent had the pandemic not occurred. See Caris Bizzaca, ‘Podcast – Jennifer Peedom: Making River and Doco Vs Drama’, Screen News, 28 March 2022, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/screen-news/2022/03-28-podcast-jennifer-peedom>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[8] The five main cinematographers are Yann Arthus-Bertrand, Ben Knight, Pete McBride, Renan Ozturk and Sherpas Cinema, the last of these being a Canadian outfit that specialises in mountain cinematography. Of the combined contributions of the twenty-three cinematographers, it isn’t clear how much of the footage was pre-existing as opposed to newly commissioned.

[9] Steve Rose, ‘“Rivers Run Through Us”: Willem Dafoe and Robert Macfarlane on Why They Made a Film of the World’s Great Waterways’, The Guardian, 18 March 2022, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/mar/18/rivers-run-through-us-willem-dafoe-and-robert-macfarlane-on-why-they-made-a-film-of-the-worlds-great-waterways>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[10] Greenwood’s piece, titled ‘Water’, was commissioned by the Australian Chamber Orchestra following his stint as composer in residence in 2012.

[11] Silvi Vann-Wall, ‘River Director Jennifer Peedom: “Our Attempts to Control Rivers Have Begun to Backfire”’, ScreenHub, 24 March 2022, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/news/news/jennifer-peedom-interview-on-river-1485605/>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[12] Although it isn’t specified in the film, this fact refers to China’s Three Gorges Dam project, which NASA scientists calculated would increase the length of a day by 0.06 microseconds. See Cutler Cleveland, ‘China’s Monster Three Gorges Dam Is About to Slow the Rotation of the Earth’, Business Insider, 18 June 2010, <https://www.businessinsider.com/chinas-three-gorges-dam-really-will-slow-the-earths-rotation-2010-6>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[13] The latter line invokes the words of naturalist John Muir, who famously wrote that ‘the rivers flow not past, but through us’. Muir, quoted in Linnie Marsh Wolfe (ed.), John of the Mountains: The Unpublished Journals of John Muir, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI, 1979, p. 92.

[14] The narration has been criticised for being ‘overly sanctimonious’, ‘platitudinous and verging on insufferable’, and ‘something even Terrence Malick would have discarded as excessive’; while, in an otherwise glowing response to the film, Schembri suggests that it ought to have been removed altogether. See Todd McCarthy, ‘Telluride Review: River’, Deadline, 5 September 2021, <https://deadline.com/2021/09/river-review-telluride-film-festival-1234827598/>, accessed 10 May 2022; Bradshaw, op. cit.; Dunks, op. cit.; and Schembri, op. cit.

[15] Other films in this vein include Baraka (1992) and Samsara (2011), both shot and directed by Ron Fricke, the cinematographer of the ‘Qatsi’ films; and nature documentaries such as Microcosmos (Claude Nuridsany & Marie Pérennou, 1996), Himalaya (Éric Valli, 1999) and Travelling Birds: An Adventure in Flight (Jacques Perrin, 2001).

[16] For example, the scores for the ‘Qatsi’ films, Baraka and Microcosmos were composed by Philip Glass, Michael Stearns and Bruno Coulais, respectively.

[17] Bill Nichols, Introduction to Documentary, 2nd edn, Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis, 2010, p. 162. According to Nichols, other examples of the poetic mode include Rain (Joris Ivens, 1929), Pacific 231 (Jean Mitry, 1949) and The Maelstrom: A Family Chronicle (Péter Forgács, 1997).

[18] The film earned over A$2 million at the box office and sits third overall on the list of highest-grossing Australian documentaries, behind the IMAX films Antarctica (John Weiley, 1991) and Africa’s Elephant Kingdom (Michael Caulfield, 1998). Sherpa sits in seventh place with a gross of A$1.28 million. See ‘All-time Top 10 Australian Documentaries at the Box Office’, Screen Australia, 3 March 2022, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/fact-finders/cinema/australian-films/theatrical-documentaries/top-documentaries>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[19] In their directors’ statement, Peedom and Nizeti suggest that River is part of a ‘planned trilogy of orchestral concert films that explore the impact of landscape on the human heart’. Peedom & Nizeti, ‘Directors’ Statement’, in Madman Entertainment, River press kit, 2021, p. 3.

[20] River dedicates a lengthy sequence to such imagery, which the film’s press kit likens to ‘gorgeous artistic renderings of stands of trees’. Madman Entertainment, ibid., p. 6.

[21] As digital media scholar Francesca Sobande contends, the slogan camouflages structural inequalities in society, while its ‘commodified construction of “we” dismisses the experiences of those who are most at risk and worst affected by COVID-19’. Sobande, ‘“We’re All in This Together”: Commodified Notions of Connection, Care and Community in Brand Responses to COVID-19’, European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 23, no. 6, 2020, p. 1036.

[22] In her capsule review of the film, Marina Ashioti suggests that the pairing of this music with footage of heterogeneous Indigenous people ‘points towards a historical fixation that the Western world has with “primitivism” – one that fosters a utopian longing for a pre-industrial way of life through a return to nature’. Ashioti, ‘River’, Little White Lies, 17 March 2022, <https://lwlies.com/reviews/river-2/>, accessed 10 May 2022.

[23] Eric Hynes, ‘Where Eagles Dare’, Film Comment, July/August 2018, p. 48.